Uchiyama Gudō (内山愚童) was born May 17, 1874, in Niigata Prefecture, Japan. He came from a family of rural woodworkers, and learned to carve Buddha statues from his father at an early age. When he was sixteen, his father died, which lead Gudō to renounce worldly life and join the Soto Zen sect, ordaining as a novice monk when he was 23. He trained for seven years at various Soto training temples and in 1904 was made abbot of a small rural temple in Hakone called Rinsenji. The villagers who supported the temple were, like most tenant-farmers in Japan, very poor. Their plight, along with Gudō’s rural upbringing and early education lead him to consider the systemic causes of rural poverty.

1904 appears to have been an important year for Gudō. In addition to taking over the temple from his master, he became an avid reader of the newly published paper Heimin Shimbun (Commoner’s News), founded by influential anarchist writer Kotoku Shusui in Tokyo. Gudōs experience with rural poverty, his interpretations of Buddhist doctrines, history, and practices, and now his exposure to radical political thought lead him to an unexpected kind of “awakening”. Gudō wrote that, “When I began reading the Heimin Shimbun at that time [1904], I realized that its principles were identical with my own and therefore I became an anarcho-socialist.” Not one to wait around apparently, he promptly submitted an editorial to the paper, which was published in January of 1904, where he wrote, “As a propagator of Buddhism I teach that “all sentient beings have the Buddha-nature” and that “within the Dharma there is equality, with neither superior nor inferior.” Furthermore, I teach that “all sentient beings are my children.” Having taken these golden words as the basis of my faith, I discovered that they are in complete agreement with the principles of socialism. It was thus that I became a believer in socialism.”

Brian Victoria writes of Gudō’s temple and social ministry, “Aside from a small thatched-roof main hall, its [Rinsenji’s] chief assets were two trees, one a persimmon and the other a chestnut, located on the temple grounds. Village tradition states that every autumn Gudō would invite the villagers to the temple to divide the harvest from these trees equally among themselves.” According to another account, “Gudō also began organising meeting for the young people at the Rinsen-ji temple, reading out sections of ‘Heimin Shimbun’ and organising youth unions (青年組合). He also gave education classes teaching reading and writing, with a pinch of political indoctrination thrown in, free of charge.” From this portrait we can get a sense of Gudō’s activism at this time: he focused on supporting his community through his religious duties, while also educating, agitating and organizing mutual aid efforts in the village. In this way he played the important role of community organizer and social worker as well as cleric.

In the subsequent years, as government repression drove the socialist movement underground, Gudō continued to radicalize, coming to agree with his anarchist comrades that direct action and propaganda by the deed were necessary tactics if socialism was to prevail. In one of his more provocative statements, he wrote “If priests today are really serious about creating a paradise, they must first overthrow the government. the hand that holds the rosary should also always hold a bomb.” It seemed that Gudō only came to reluctantly embrace the praxis (or at least the threat) of propaganda by the deed, often demonized in the press as ansatsushugi (assassination-ism). What was more unusual was his willingness to speak out against war, capitalism and the emperor in a time when freedom of speech was so totally suppressed. So many of his colleagues chose to remain silent, recant their views under pressure, or side with the government despite personal reservations. The majority of Buddhist leaders at the time were actually enthusiastic supporters of the rising tide of fascist imperialism cultivated under the Meiji and Showa emperors and the military, often using religious rhetoric to justify subservience to the state and self-sacrifice in battle.

In 1908 Gudō established a secret press in the basement of Rinsenji, where he printed booklets defaming the emperor, calling on soldiers to desert, and urging peasants to refuse to pay taxes or rent and to form agricultural worker’s unions. His most infamous pamphlet, “Anarchist Communist Revolution” was so shocking to people at the time that many recipients burned their copies out of fear of the secret police discovering them. Other people were deeply inspired by it, including ironworker Miyashita Taikichi, who passed it out to strangers in the street who had gathered to see a royal procession. Miyashita and a small group of other Heimin readers would later begin a plot to assassinate the emperor with dynamite. Because of the incendiary rhetoric in his pamphlet that Gudō was eventually arrested, tried and imprisoned in 1909. During his trial, the prosecutor describe his pamphlet as “the most heinous book ever written since the beginning of Japanese history.” Quite the complement, really, if only it didn’t have such tragic consequences for Gudō and his comrades.

After Gudō spent a year in prison, the government caught wind of the assassination plot, seizing explosive materials from Miyashita and others. Seeing an opportunity to crush the socialist movement, prosecutors arrested dozens of radicals from across the country – including Gudō, who had been in jail the entire time – on circumstantial evidence, and brought Gudō to trial again, sentencing him, along with fellow anarchists Kotoku Shusui, Kanno Sugaku, and twenty one others, to execution. This group included three other Buddhist priests, Takagi Kenmyo, Sasaki Dogen and Mineo Setsudo, who later had their sentences commuted to life in prison, where they would all die. Gudō was hanged on January 24, 1911 at the age of thirty seven. It was recorded that as he approached the scaffold, “he gave not the slightest hint of emotional distress. Rather he appeared serene, even cheerful–so much so that the attending prison chaplain bowed as he passed.”

Emma Goldman and other American anarchists who knew Kotoku Shusui from his time living in the US began an international solidarity campaign to free the accused, urging readers of Goldman’s Mother Earth magazine to support them. Unfortunately these efforts did not succeed. This was thankfully not the end of the Japanese anarchist movement.

This trial and execution later came to be called the “High Treason Incident”, and much like the 1886 Haymarket affair in Chicago, shocked and radicalized a number of the next generation of Japanese anarchists, including feminist historian Takamure Itsue and Zen priest Ichikawa Hakugen. Many anarchists also managed to escape trial, including influential writer Osugi Sakae and his partner Ito Noe, as well as those who fled abroad, like Ichikawa Sanshiro, who returned to found radical trade unions in the 1920s and the Japanese Anarchist Federation in 1946.

Gravestone of Uchiyama Gudo at Rinsenji temple

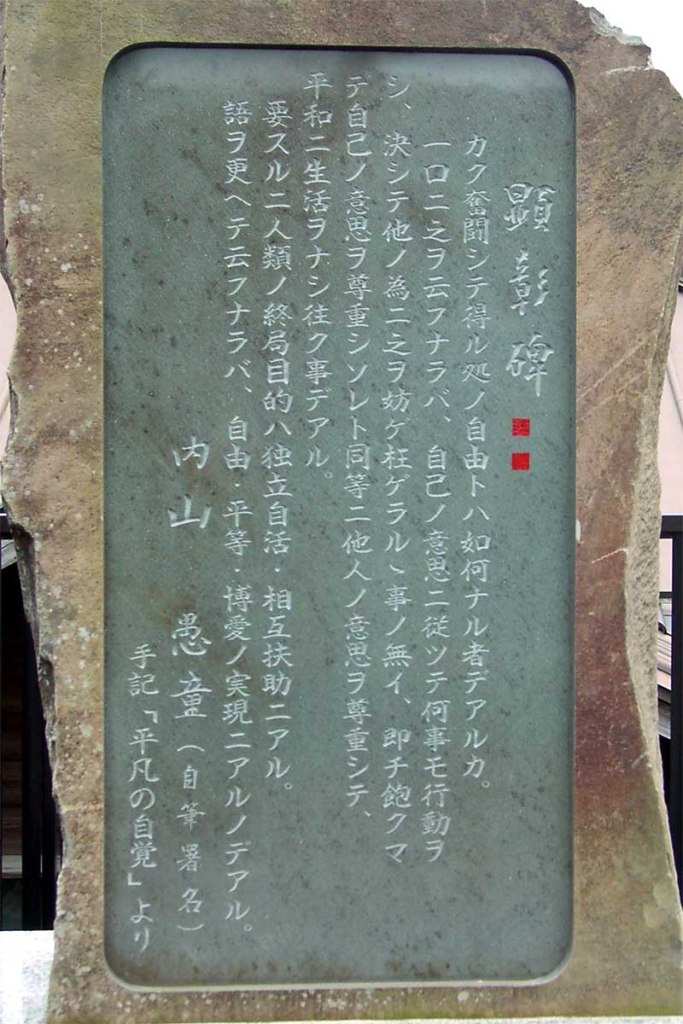

Gudo’s epitaph.

Though he did not leave much theoretical work behind, Uchiyama Gudō’s life and work is one of the best examples we have of a lived Buddhist Anarchism during the heyday of the global anarchist movement. As more people become interested in him, I suspect that he will come to be known as the first buddhist-anarchist revolutionary and martyr. Gudo’s writing on revolutionary love and self-sacrifice certainly suggest that be began to see himself this way. I have mixed feelings about this.

Gudō was certainly a sincere and committed anarchist revolutionary; as a Buddhist he was deeply realized and compassionate Zen priest; but beyond or beneath all of that he was an ordinary human just like any of us. It is important to remember the aspects of historical and living figures that don’t fit inside of the big dramatic narratives its writers and actors tell. History, I think, is unavoidably a kind of fiction, and humans, let alone nature itself, seldom fit perfectly inside the boxes and categories and models we ascribe to them. It would do everyone credit to not dehumanize those who have come before us with our own idealistic projections, neither hero-worshipping nor demonizing, but acknowledging, listening to and learning from what they made of their life through thoughts, words and actions.

Nevertheless, I have come to feel a deep sense of affinity with Gudō and his sincere approach to dharma and social justice. It is thanks to his biography that I started to explore this question of “Buddhism-Anarchism” seriously.

It would appear that his grave at Rinsenji is a popular destination for Japanese engaged Buddhists, where he is better known as Gudō-shi (師), a beloved and kindhearted Zen “fool” (His Dharma name, 愚童, means “fool”; Gudō-shi 愚童師 basically means “Master Fool”) and as a person who “planted Buddha seeds”, with his courage and revolutionary sense of justice.

After reading his work and life story in Rambelli’s book I was moved to write a few verses for him, which at the risk of embarrassing myself, I will share here.

Gudō

They say all beings have the Buddha nature

and that means you folks right here

these persimmons too, these chestnuts we’ll share

Budding, blooming, becoming

Act as if all beings as your relatives, parents, children

because they are

get together and take back the land you work

what is unborn cannot be owned

but it can be shared

this dharma is without high nor low, rich nor poor, masters nor slaves.

inherited will, embodied, the incessant heartbeat:

freedom, freedom

ripening, struggling, being

they put you in a noose for your love, your doubt and your rage

for teaching the children, comforting the oppressed and suffering

and refusing to bow

to the powers of this world

falling, dissolving, decomposing

and so you drop your body once again plunged into the stream

tossed and tumbling

scattered and scarred

open, weary

smiling

another foolish dharma seed

something which Law

cannot name, cannot claim and cannot hang

Some thing which is No thing at all

going, gone, gone

what we always were

are

will be

boundless blue sky

in other words: love

&

because this love is selfless

because this love is change

because this love is pain

because this love is empty

it is foolish, it is free,

gone beyond

thus:

gone beyond beyond

another world is possible

because it is possible

It

will

be

…the fruit, the seed,

and the fool

always returning to

THIS

References

Brian Victoria “Zen at War” Chapter 3: Uchiyama Gudō Radical Sōtō Zen Priest

Fabio Rambelli “Zen Anarchism: The Egalitarian Dharma of Uchiyama Gudo”

Terebess.hu 内山愚童 Uchiyama Gudō (1874-1911)

Ishikawa Rikizan “The Social Response of Buddhists to the Modernization of Japan: The Contrasting Lives of Two Soto Zen Monks“

Kameno People who plant Buddha seeds: Uchiyama Gudō

Thank you for making this post available. I look forward, and support, your ongoing efforts to explore and delineate the political dimensions of the Buddha Dharma.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Brian! I’d love to talk to you about some of these ideas. Would you mind sharing your email address with me?

LikeLike

Dear ‘Reedwing’,

Thanks for your response. Like you, I would enjoy being in direct contact. I’m sure we have much to share. My e-mail address is: brianvictoria1@yahoo.com. I look forward to hearing from you.

With best wishes,

Brian

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Brian. I sent you an email but I’m not sure it got through. Maybe it went to your spam folder. Could you try sending me a message at reed.ingalls@gmail.com?

LikeLike

I just came to Japan to attend the birth of my first child. I am a practising Buddhist who started his journey in a Chinese temple in the Pure Land tradition some ten years ago before I went on a 1000days pilgrimage all around East and South East Asia primarily working on farms, painting murals in temples, hitch-hiking, begging for food and eventually building my own Bamboo Zazendo in the Malaysian Jungle. I am so glad that you made this post introducing me to the life of Uchiyama Gudo I could not help breaking in to tears reading about him (its been a while). I wish to visit his grave since I am in Nagano and not to far away. If you are in Japan perhaps we could meet somewhere around the temple for a cup of tea.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, thanks for sharing your story Marcus. I had a similar, if shorter, adventure in Japan back in 2013, though I haven’t returned since. You should definitely visit Gudō’s grave. Send some pictures if you can! Unfortunately, I am not in Japan, so I can’t meet you for a cup of tea at the moment.

LikeLike