Kim, Yong-ha

Note: This is another machine translation. I apologize for any errors made. It should not be published as an official translation or substitute for the original work of the author.

Abstract

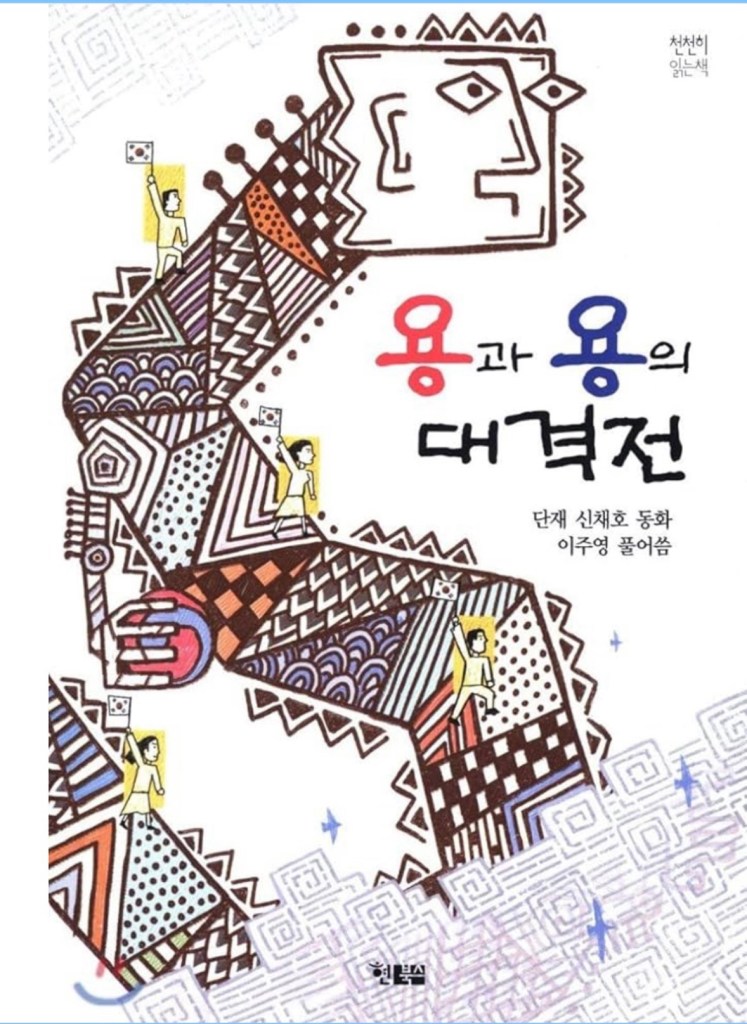

This study examines the political narrative aspects of Buddhist anarchism and popular divination beliefs as they appear in Shin Chae-ho’s The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons (龍과 龍의 大激戰). Shin Chae-ho’s thought in his later period may be characterized as Buddhist anarchism. During the early 1920s, he lived as a monk. After going into exile in China, he devoted himself to Buddhist scriptures such as The Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna and the Vimalakīrti Sūtra. He attempted to combine Buddhism with anarchism.

Shin recognized the limitations of modern thought and perceived the violence inherent within it. Modern thought concealed the contradictions of capitalism and colonialism, and for this reason he sought to dismantle its structure. He regarded the grassroots people as the subject of revolution and believed that they possessed destructive power capable of dismantling the authority of modern thought.

As noted above, Shin sought to combine Buddhism with the worldview of the grassroots people. However, due to practical and realistic difficulties, he found this project difficult to realize directly and instead turned to fictional writing. Fiction allowed for the possibility of an imagined community, and these ideas are reflected in The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons.

The narrative characteristics of The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons are as follows.

First, the work seeks to eradicate the ill-fated relations and misdeeds of the pre-heaven era and to dismantle the structure of the pre-heaven, including the modern epoch.

Second, it expresses the emptiness (śūnyatā, 空) of the no-self subject (nirātman-subject, 無我-主體). The no-self subject indicates that the collective of the grassroots people is formed as a subversive subject.

Third, the no-self subject employs counter-violence for liberation (vimokṣa, 解脫), rejecting modern violence and engaging in purposeful struggle for the post-heaven era.

Fourth, the eschatology of The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons is expressed through divination and the curse of the dragon, reflecting the grassroots people’s reliance on divination in everyday life.

Through this analysis, the work demonstrates the relationship between Buddhist anarchism and the divinatory eschatology of the grassroots people.

Keywords: Buddhist anarchism; no-self subject (無我-主體); emptiness (空); counter-violence; divinatory eschatology

1. Introduction

This paper aims to analyze the political narrative patterns of Buddhist anarchism and divination beliefs as they appear in The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons.[1]

A review of prior studies on The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons reveals the following tendencies. Research on anarchism in the work[2] has generally focused only on the fact that Shin Chae-ho reflected anarchist ideas in his fiction. As a result, these studies have tended to overlook the fact that he subjectively transformed anarchist thought in his own way.

Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the fact that Shin lived as a monk after going into exile in China during the 1920s. Perspectives that examine his intellectual affinity with Buddhist thought remain insufficient. If we consider that Shin underwent Buddhist experiences before and after adopting anarchism,[3] it is reasonable to infer that his reflections on anarchism were underpinned by a philosophical affinity with Buddhism.[4]

Shin avidly read Buddhist scriptures and critically appropriated a Buddhist worldview.[5] During the 1920s, he attempted to construct a unique worldview that fused anarchist thought with Buddhist perspectives. The vastness of space and time and the cosmic scale of events depicted in The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons may be regarded as a modern re-presentation of the Buddhist imagination found in Buddhist scriptures.[6] Moreover, it is noteworthy that monks frequently appear as characters in his post-exile fiction.[7]

With these points in mind, this study proceeds on the premise that Buddhist modes of thought underlie the anarchist ideology expressed in The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons. Accordingly, it analyzes the narrative strategies of the work from the perspective of Buddhist anarchism.[8]

2. The World of Emptiness of the No-Self Subject

This section seeks to elucidate the empty (空) world of the no-self subject. In particular, it analyzes the meaning of “0,” which signifies the substance of the dragon, from the perspective of emptiness.

In The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons, the dragon is not represented as a concrete or fixed entity. Rather, its essence is expressed through the symbol “0.” However, the “0” of the dragon differs from the mathematical concept of zero. Mathematical zero merely occupies a place value without possessing substantive reality, whereas the dragon’s “0” can become one, two, three, four, and up to ten, one hundred, one thousand, or ten thousand. Likewise, while mathematical zero lacks material substance, the dragon’s “0” can become a gun, a sword, fire, lightning, or any other form of terror.

The text states that although the dragon is expressed as “0” today, tomorrow the enemy that stands opposed to the dragon will be eliminated as “0.” When this occurs, the empire will become “0,” heaven will become “0,” and all other ruling powers will also become “0.” Only when all ruling powers have been reduced to “0” will the dragon’s constructive reality become visible. This passage appears under the heading “The History of the Dragon.”[19]

In the narrative, the dragon brutally kills Aso Christ, the only son of the King of Kings (Shangdi). Enraged by the dragon’s atrocities, Shangdi mobilizes the heavenly police and intelligence forces and orders the dragon to be hunted down. Despite extensive investigations by the forces of heaven, the true identity of the dragon remains unknown. However, The Earth Nation People’s Newspaper publishes an article containing clues related to uncovering the dragon’s identity. According to this report, the dragon’s true form is marked as “0,” and it is emphasized that this “0” is fundamentally different from mathematical zero. The dragon’s “0” transcends the stage of nothingness (無).[20]

The “0” symbolizing the dragon corresponds to the Buddhist concept of emptiness (空). Emptiness does not signify mere nonexistence but rather denotes the denial of fixed essence and the dismantling of substantialized identities. In this sense, the dragon’s “0” signifies a no-self subject that negates all forms of fixed authority and domination. This no-self subject does not exist as an individualized entity but rather emerges through the collective association of the grassroots people.

The no-self subject perceives the modern world as empty and, through this recognition, overcomes the violence embedded within modernity. The structure of the pre-heaven era—including the modern epoch—is not fixed or immutable but is instead contingent upon the degree to which the grassroots people become self-aware of the contradictions inherent in modern society. As such, the no-self subject constitutes a subversive force capable of dismantling the oppressive structures of the pre-heaven era.

This conception aligns with Buddhist thought, which emphasizes correct insight into the mind and enlightenment while rejecting all external authority. Such a perspective resonates with the spirit found in The Record of Linji (Linji Lu), which denies the conceptual world that leads humans into delusion and rejects all forces that oppress the inner mind and lived reality. The dragon, as an anarchistic symbol, thus embodies a Buddhist-inspired rejection of authority grounded in the realization of emptiness.[34]

3. The Evil Relations and Evil Karma of the Pre-Heaven Era

This section examines the forms of evil relations and evil karma manifested in the pre-heaven era. The pre-heaven era refers to a world governed by antagonistic logic, encompassing modern society itself. When individuals of the pre-heaven era fail to recognize the solidarity of minds, the result is the reproduction of oppressive structures.

In The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons, heaven represents a violent system sustained through authority and domination. The King of Kings (Shangdi) symbolizes absolute power, while heaven operates as a regime that maintains order through coercive force. The empire and heaven together constitute the institutional embodiment of pre-heaven violence.

The dragon, as a figure of anarchistic resistance, directly confronts this structure. By assassinating Aso Christ, the son of Shangdi, the dragon exposes the false sanctity and legitimacy of heavenly authority. This act is not presented as an isolated instance of cruelty but rather as a symbolic disruption of the ideological foundations that uphold the pre-heaven system.

Within this narrative framework, heaven attempts to suppress the dragon through surveillance, policing, and military force. Angels are mobilized to hunt down the dragon, but they remain incapable of grasping its true nature. This inability signifies the limits of pre-heaven epistemology: authority cannot comprehend a subject that lacks fixed essence.

One angel, recognizing that heaven can no longer be sustained as its end approaches, sets out to locate Shangdi. The angel encounters Paul in Jerusalem and the Great Emperor of the Qing dynasty in Beijing and inquires about Shangdi’s whereabouts. Both figures dismiss and ridicule the angel. In particular, the Qing emperor asserts that the ritual offerings performed for the purpose of imperial stability are nothing more than theatrical performances staged on days celebrated by the people.

The angel, however, refuses to accept that the pre-heaven era has reached its end through violent liberation and instead clings nostalgically to the old order. The narrative portrays the angel as a figure incapable of perceiving the flow of historical change. After being slapped by both Paul and the Qing emperor, the angel is depicted as someone who fails to comprehend the direction of the times.

Eventually, the angel encounters an old Taoist who earns a living by performing divination and receiving ten coins as payment. The angel requests a divination in order to discover a means of locating Shangdi.

“This is not an ordinary divination, but a divination to find our Lord. We do not know where our Lord has gone…”

The Taoist laughs and remarks that it is rare in the present age for anyone to wander about searching for a lord, calling the angel a truly loyal servant. After shaking the divination tube, the hexagram Qian zhi Dun (乾之遯卦) appears. The Taoist is greatly startled and exclaims:

“Ah—Qian signifies Heaven, that is, Shangdi; Dun signifies retreat or flight. It seems you are not a servant searching for your lord, but an angel seeking a Shangdi who has fled.”

Upon hearing this, the angel cannot help but be astonished and kneels down, respectfully asking to be shown the place where Shangdi resides.

This episode reveals that even Shangdi, the supreme authority of the pre-heaven era, has become a fugitive. Heaven’s collapse is thus depicted not as a sudden catastrophe but as an inevitable consequence of accumulated evil relations and evil karma. The pre-heaven order, sustained through violence and repression, contains within itself the conditions of its own dissolution.

4. The Eschatology of Incantation and Divination

In a situation where heaven and earth are inverted, heaven is extinguished and the earth-nation comes into being.

The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons presents a dual structure of the psychological condition of the grassroots masses. The grassroots masses are beings who have anthropologically become conscious of the contradictions of the world. By contrast, the people are merely beings who remain unconscious of the contradictions of the world. The people fail to perceive the falsity of heaven, represented by the King of Kings (Shangdi), and instead rely on his authority and power, expressing wishes solely for their own personal safety and well-being.

The grassroots masses, however, transcend the individualistic nature of the people and come to realize that the metaphysical system symbolized by heaven is fictitious. They psychologically yearn to transform heaven into the earth-nation. To the extent that the people positively acknowledge the advent of the Maitreya, the oppressive force of heaven becomes all the more powerful.

“Nari-shinda, nari-shinda, the Maitreya (dragon) descends.

The New Year has come, the New Year of the cyclical year has come,

the Maitreya descends upon East Asia.”[37]

“The dragon has come, the dragon has come;

now is the end of heaven.”[38]

The grassroots masses pray for the appearance of the Maitreya. They regard the Maitreya as a being who will eliminate their everyday suffering. However, the Maitreya betrays the expectations and hopes of the grassroots masses. The Maitreya appears not as a savior who provides comfort but as a force that negates the existing order.

Through this narrative, the work reveals that the grassroots masses’ eschatological expectations are mediated through incantation and divination beliefs. Divination functions as a practical means through which the grassroots masses interpret historical transition and anticipate the collapse of heaven. Rather than serving as a passive form of superstition, divination belief operates as a political mechanism that sustains the antagonistic consciousness of the grassroots masses toward the pre-heaven order.

The eschatology presented in The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons thus differs fundamentally from religious eschatology premised on salvation or redemption. Instead, it is grounded in the anticipation of destruction and inversion. Heaven is not to be perfected but abolished; the pre-heaven era is not to be reformed but brought to an end.

Through incantation and divination, the grassroots masses maintain psychological readiness for the advent of the post-heaven era. Divination belief, therefore, functions as a narrative device that preserves revolutionary tension and defers reconciliation with the existing order.

5. Conclusion

In summary, The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons can be understood as a work that politically mobilizes divination belief in order to provoke awareness among the grassroots masses of the contradictions inherent in their world and to sustain the rebellious orientation of an awakened populace toward the future.

Centered on a worldview of Buddhist anarchism, the work encourages the grassroots masses to recognize the contradictions of their lived reality and employs divination belief as a political narrative device to preserve their antagonistic stance toward the existing order. The dragon, symbolized as “0,” represents the no-self subject grounded in emptiness (空), negating all fixed authorities and oppressive structures.

The pre-heaven era, which encompasses modern society, is depicted as a violent system sustained by antagonistic logic, authority, and repression. Heaven and empire are revealed as fictitious metaphysical constructs that legitimize domination. Through the concept of violent liberation, the work asserts that the transition to the post-heaven era cannot be achieved through reform or reconciliation but only through the dismantling of pre-heaven structures.

Divination belief plays a crucial role in this process. For the grassroots masses, divination functions as a means of interpreting historical change and anticipating the collapse of heaven. It sustains revolutionary consciousness by deferring closure and maintaining eschatological tension. In this way, divination belief is not portrayed as mere superstition but as a form of political imagination that enables resistance.

Bang Yeong-jun. “Buddhist Characteristics of Anarchism.” Buddhist Review, no. 6, 2001.

Ultimately, The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons demonstrates the convergence of Buddhist anarchism and the divinatory eschatology of the grassroots masses. By integrating the Buddhist concepts of no-self and emptiness with anarchist resistance to authority, Shin Chae-ho constructs a narrative that envisions the destruction of pre-heaven violence and the emergence of a post-heaven world grounded in collective liberation.

References

Monographs

Kim, In-hwan. The Genealogy of the Modern Korean Novel. Minumsa, 2001.

Kim, Jeong-bae. Ancient Korean History and Archaeology. Sinseowon, 2000.

Kang, Man-gil (ed.). Shin Chae-ho. Korea University Press, 1990.

Gwang Myeong. An Introduction to Buddhist Studies. Solgwahak, 2009.

Go Ik-jin. A Systematic Understanding of Buddhism. Gwangnyeok, 2008.

Murayama Jijun. Divination and Prophecy in Joseon Korea. Translated by Kim Hee-kyung, Dongmunsun, 2005.

Lee Hye-hwa. Mir: Everything about Dragons. Book by Book, 2012.

Sakai Takashi. The Philosophy of Violence. Translated by Kim Eun-joo, Sannun, 2007.

Shin Yong-guk. Dependent Origination: A Revolution of Cognition. Haneulbook, 2009.

Journal Articles

Kim, Gyeong-bok. “Dan-jae Shin Chae-ho’s Literature and Anarchism.” Korean Language and Literature, no. 30, Busan National University, 1993.

Kim, San-chun. “Angelology and Dante’s Concept of Angels.” Journal of the Korean Society of Aesthetics and Art, no. 25, 2007, pp. 276–277.

Kim, Seong-jin. “A Study of Shin Chae-ho’s Textual Practice: The Relationship between Thought and Writing.” Seoncheong Eomun, no. 28, 2000.

Kim, Taek-ho. “A Study on the Unity of Shin Chae-ho’s Thought.” Korean Literary Criticism Studies, vol. 25, 2008.

Kim, Hyun-joo. “A Study on the Transformation of the Hero in Shin Chae-ho’s Fiction: Focusing on the Deepening of Anarchist Thought.” Eomunhak, no. 105, 2009.

———. “A Study of Character Formation in Shin Chae-ho’s Post-Exile Fiction: In Relation to the Transition from Modernity to Postmodernity.” Hanminjok Eomunhak, no. 56, 2010.

Min Chan. “The Trajectory of Dan-jae’s Fiction and the Magnetic Field of Tradition.” Journal of the Humanities, no. 34, Daejeon University Institute of Humanities, 2002.

———. “Content and Form of Dan-jae’s Novel The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons.” Eomun Research, vol. 48, 2005.

Park Jung-ryeol. “Revisiting Dream Heaven and The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons: Rewriting History through Oneiric Allegory.” Korean Literary Theory and Criticism, no. 33, 2006.

Seo Eun-seon et al. “The Literary Figuration of Shin Chae-ho’s Anarchism: The Inversion of Heaven and Dragon Imagery.” Collected Papers on Korean Literature, no. 48, 2008.

Shin Gyu-tak. “Kill the Buddha, Kill Bodhidharma.” Philosophy and Reality, no. 50, 2001.

Shin Hyun-sook. “The Development of Emptiness Thought in Mahāyāna Buddhism.” Journal of Buddhist Studies, vol. 27, 1990.

Yeo Jeong-sam. “A Philological Study of Divination and Sacrificial Rituals.” Sogang Humanities Journal, no. 26, 2009, pp. 227–228.

Lee Dong-sun. “Dan-jae’s Fiction Viewed through Oppositional Structures: Focusing on The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons.” Gaesin Eomun Research, no. 2, 1982.

Lee Byeong-uk. “Buddhist Views on Violence.” East–West Thought, no. 15, 2013, pp. 59–63.

Lee Ji-hoon. “A Study of Shin Chae-ho’s Anarchism and The Fierce Strife between Two Dragons.” Korean Modern Literature Studies, no. 8, 2000.

Online Sources

Im Heon-yeong. “Buddhist Imagination and Literature.” Yusim, 2006.

“Buddhist Anarchism.” Wikipedia.

Original Korean Article. Please let me know of any errors or inaccuracies in the machine translation