Archives of the buddhist peace fellowship

The Buddhist Peace Fellowship was, at least in the West, the most influential organization of the “Engaged Buddhism” tendency in the late 20th Century. It is still active today but has declined in membership and influence since its heyday.

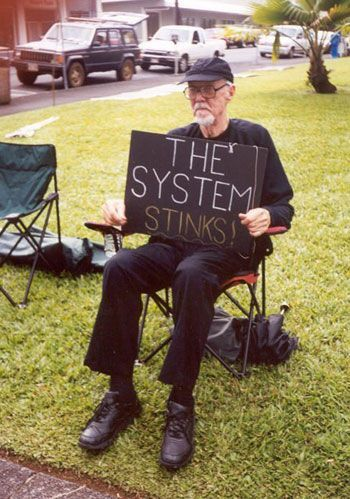

To understand the politics of the BPF it is especially important to understand the politics of its founder and spiritual anchor, Robert Baker Aitken (1917-2010).

From an obituary in the LA Times:

His introduction to Zen came with the outbreak of World War II, when he was a civilian construction worker on Guam. He was captured by Japanese troops in 1942 and spent the duration of the war in an internment camp in Kobe.

In the camp, a Japanese guard lent him a copy of British scholar R.H. Blyth’s “Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics.” Aitken was fascinated and read the book many times.

After the 10th reading, the world “seemed transparent,” Aitken wrote years later, “and I was absurdly happy despite our miserable circumstances.”

In 1944, when several camps were consolidated in Kobe, he met Blyth, who had been teaching in Japan when he was detained as an enemy alien. Aitken spent the next year in constant conversation with Blyth; and when they were released at war’s end, he decided he would learn meditation under a Zen master.

Aitken returned to Hawaii and enrolled in the University of Hawaii, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in English literature in 1947 and a master’s degree in Japanese studies in 1950. His master’s thesis on the great haiku poet Basho became the basis for his book “A Zen Wave” (1978).

He was working in a bookstore in Los Angeles in the late 1940s when he began to study with Nyogen Senzaki, an itinerant Zen monk who had settled in California in the 1920s. Aitken later went to Japan to train under Nakagawa Soen Roshi, who authorized him to establish a meditation group in his home in Hawaii in 1959. He was ordained in 1974.

During his youth, he developed an extensive knowledge of anarchist and Marxist literature, as well as a familiarity with political action. While the strength of the anarchist movement in the West had faded by the time Aitken was an adult, the memory must have still been fresh, and many of its writers and activists were still alive. This intimacy with anarchism appeared to have influenced and been influenced by his career in Zen. In an interview for the Fall 2006 issue of Turning Wheel, he told Susan Moon that he first became an activist, “When I was interned in a camp, in Kobe, Japan, in World War II, American B-29s burned the city of Kobe in two bombing raids. The camp was on the hill above the city, where the planes came past us as they made their turnaround-the bomb bays were open and we could see the racks of bombs. The next morning, we saw refugees-women and old men and children-filing up the trail past our camp toward villages behind the city. The juxtaposition of those two events-the night before and the next day-hit me pretty hard, and I resolved at that point that in addition to making my life one of Zen study I was also going to make it a life of social action.“

Moon: “Did you think at that time that they would be

two separate things?”

Aitken: “No, they couldn’t be, because there was just one me. And so, long before I was able to get organized as a Zen student, I was going on marches and taking part in meetings, in resistance to further development of nuclear bombs. It was really an anti-nuclear movement. But it was all kind of namby-pamby when I look back on it.”

Like many “Buddhist anarchists”, as they were now calling themselves, Aitken sensed a fundamental unity of the two views, perhaps as expressions of the same underlying dynamic. This dynamic I have identified as a worldview of absolute freedom based on absolute negation, a dialectical and contemplative practice which most figures I have studied have expressed in one way or another. And from a practical point-of-view, there really was just one of him (at least until the BPF came around). A life which is called in two seemingly contradictory directions must, for it to work, harmonize them. A life–koan as these things are sometimes called.

To give you a sense of Aitken’s political views, I will include a couple of long quotations. The first is an interview with Aitken conducted by Barbara Gates and published in the Spring 1993 issue of “Inquiring Mind”, titled Buddhist as Revolutionary.

RA: I think that the revolutionary Buddhist is an anarchist in the true sense of anarchism, that is to say the person who takes individual responsibility and lives the life of the Dharma as best she or he can within and beside the system. To do this, the individual must gather with like-minded friends.

I like the model of the so-called “base communities.” These are small groups of up to 15 members who meet frequently for sharing, planning and perhaps religious practice, who conduct a program of community service, or who might have individual projects. For example, the group might issue a newsletter on a particular theme, or manage a co-op, or do prison visitation or plan a festival. Or it might have a specific role in a political movement.

Catholic Worker houses and their networking system form a good example of the base community ideal in our North American society. Each house is autonomous, conducting its own program of feeding and perhaps housing the poor, but each is particularly inspired by the writings of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin. So their programs are very similar, and they are in touch with each other informally and through their newsletters. Liberation Theology, primarily found in Central and South America, functions through base communities, sometimes just keeping the spirit alive through sharing, sometimes taking part in large political movements.”

The Catholic Worker houses are base communities though the members do not generally use the term. Probably Peter Maurin was influenced by nineteenth-century anarchism and the work of Gustav Landauer and others who formed networks of what Landauer called the Socialist Bund communities. In the Spanish Civil War, the anarchists were grounded in eighty years of working in base communities. They formed grupos de afinidad which translates as “affinity groups” and conducted their campaigns through these more or less autonomous cells. The notion of affinity groups was taken over by the Movement for a New Society, and we who marched and demonstrated in the late sixties and early seventies were always organized in affinity groups for demonstrations. Each group had a spokesperson, a first-aid person and a security person. Each leader got special training, and we networked and made larger group decisions through the spokesperson.

Latin America and the Philippines are full of these little cells of people who are working together and networking with other cells. Marcos was overthrown as a result of the work of these base communities in the Philippines. The achievements of the overthrow didn’t last, but you can be sure that the base communities are still meeting and still working.

My impression is that in South and Central America base communities are really like-minded friends and friends with similar talents. They get together and find that they have an affinity for working with computers or they have an affinity for carpentry. Some of them get together to talk about religion, to pray together or to share together what’s happening in their lives. They find their little niche in that way and then network with others who have different kinds of affinities.

Now we need to form these affinity groups and set up our own systems, our own banks, our own stores, our own schools. This means starting from scratch. The affinity groups in South America didn’t pop out of a vacuum. They developed through many years of organizing. So we’ve got our work cut out for us.

IM: But isn’t there a danger that Buddhists will become ghettoized by removing themselves?

RA: I don’t favor the kind of co-ops that, for instance, the Krishna people have set up where you don’t get a job unless you are a Krishna. We must indeed avoid that kind of ghettoizing and exclusiveness, as well as the self-righteousness that comes out of it. I would like to see Buddhists helping with the leadership of an anarchist movement and encouraging, for example, Native American affinity groups or helping the Quakers and Catholic Workers. I see no reason why there couldn’t be base communities of mixed religious antecedents.

Next, an excerpt from Robert Aitken’s address to the Buddhist Peace Fellowship in June, 2006, called Taking Responsibility:

Buddhism is anarchism, after all, for anarchism is love, trust, selflessness and all those good Buddhist virtues including a total lack of imposition on another. During the 19th and even early 20th century, European and then American anarchists occupied respected podiums on lecture circuits from Boston and New York and across the continent to Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles At length that roster of distinguished speakers included the anarchist Har Dayal, author of The Bodhisattva Doctrine in Sanskrit Literature, an important text that belongs in all our libraries, who came to the American lecture circuits from India by way of London to edify our grandparents and their parents.

Today we’re up against the iron face of carefully crafted public opinion. From the

Haymarket tragedy in 1886 to the trials of Sacco and Vanzetti in 1921, there was in the United States almost half century of concerted, bloody minded, and ultimately successful endeavor to erase anarchism and its devotees from civilized discourse. To this day, even in a gathering like our own, the very word “anarchist” evokes an unkempt foreigner with a bomb about to go off in his back pocket. It might seem better to keep the two words in separate little boxes.

That doesn’t work. Go to Google, type in the words “Buddhist Anarchism,” and

stand back. The number of hits will surprise you. Moreover, except for references to Gary Snyder’s article by that name in the first Journal for the Protection of All Beings back in 1962, all the hits will be in Classical Buddhism, in the Buddha’s own words. Gary’s piece referred to the Huayan Sutra—well taken, but there is a world of other possible Mahayana references. The “Three Bodies of the Buddha,” for example. Everything really is empty, personally interconnected, and precious in itself. We don’t need some guy in saffron robes to tell us so. Apart from Google hits and from any kind of Buddhism, our ordinary common sense tells us so. Anarchism makes sense, for all the iron faces, for all the nooses of the Haymarket tragedy and all the subsequent ruthless persecutions and prosecutions and executions. The lonely, quavering voice of Lucy Parsons puts us to shame.It’s time to put ourselves in a position where we have nothing to protect. No

group ego. No name, no slogan. Like King Christian X of Denmark we can all wear the

yellow star. We can all wave the black flag, no color and no design. It is design that does us in. There is only one thing that works in the face of the iron faces, and that is decency. By being decent, I don’t mean being nice. I mean Mahayana responsibility. It isn’t nice to block the doorway. Decent Mahayana conduct means behaving appropriately. It is surely appropriate in these days of justifying torture and white phosphorous as weapons, to hold up an inexorable mirror to the fiends who are raising hell in our name—and then following through with an essential agenda that is not necessarily legal, like smuggling medicine to Iraqi people—the program of Voices in the Wilderness until the situation became too dangerous—or setting up a half-way house for recently released prisoners, like the Olympia Zen Center, or feeding the poor, five days a week, week in and week out for years and years, like Catholic Worker houses across the country. The essential agenda is not a hobby, after all.

So, we can see that Aitken was an interesting figure, to say the least. One of those rare activists to bridge the gap between the radical worker’s movements of the turn of the 20th century and the new social movements of the 1960’s onward.

The “about” section of BPF’s website also documents the influence of anarchism in its own organizational history. I think that it is safe to speculate that the influence of the BPF on its members and of its members on the broader Western Buddhist movement also spread this spirit of spiritual radicalism throughout the milieu, at least in some diluted form.

“In 1968, Buddhist poet Gary Snyder wrote a challenging piece called “Buddhism and the Coming Revolution.” In it, he says, “The mercy of the West has been social revolution; the mercy of the East has been individual insight into the basic self/void. We need both.” Ten years later, in 1978, the Buddhist Peace Fellowship took form as the first organizational flower of socially engaged Buddhism here in the West.

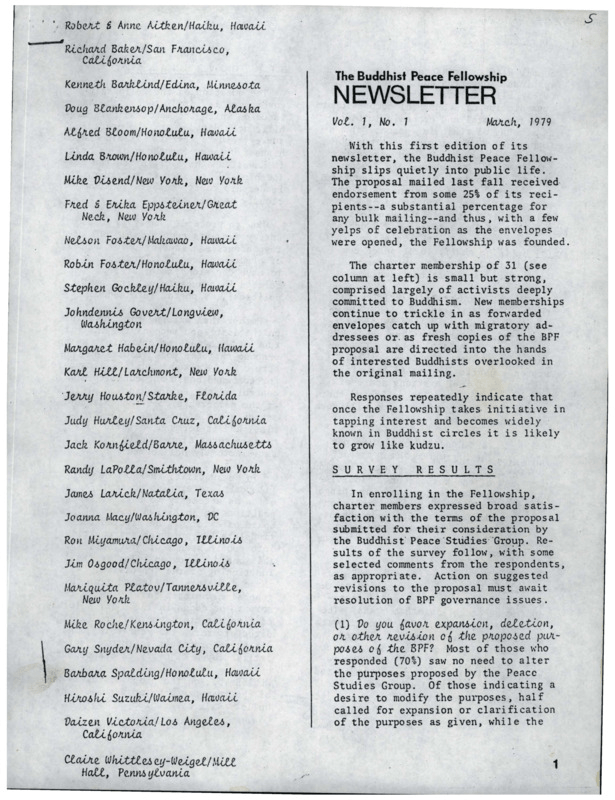

BPF was born on the back porch of the Maui Zendo, co-founded by Nelson Foster, Robert and Anne Aitken. The spark for BPF flew from Roshi’s in-depth study of 19th and 20th century anarchism and his long experience as an anti-war and anti-military activist. They were soon joined by Gary Snyder, Joanna Macy, Jack Kornfield, Al Bloom, and many others. Its ecumenical approach to the Dharma was a matter of principle, a real strength in the face of Buddhism’s sectarian history. At the start, there was a circle of friends, predominantly Euro-American Zen practitioners, most clustered in Hawaii and the Bay Area, with the rest scattered across the States. After a year there were only about fifty members, but it was a real network nonetheless, linked by friendship, common purpose, and by the dedicated work of Nelson Foster, who regularly published the newsletter and maintained active correspondence with members. Christianity, Judaism, and Islam have long nurtured forms of spiritually-based activism and social transformation.

BPF itself emerged as a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, an interfaith umbrella of nonviolent peace and justice organizations. In those first years the ties between BPF and FOR were close and very encouraging for lonely Buddhist activists. From this branch of the peace movement, with its links to Jesus, Gandhi, Thomas Merton, and Martin Luther King, we began to find ways consonant with and parallel to the Dharma to explore suffering and social change.

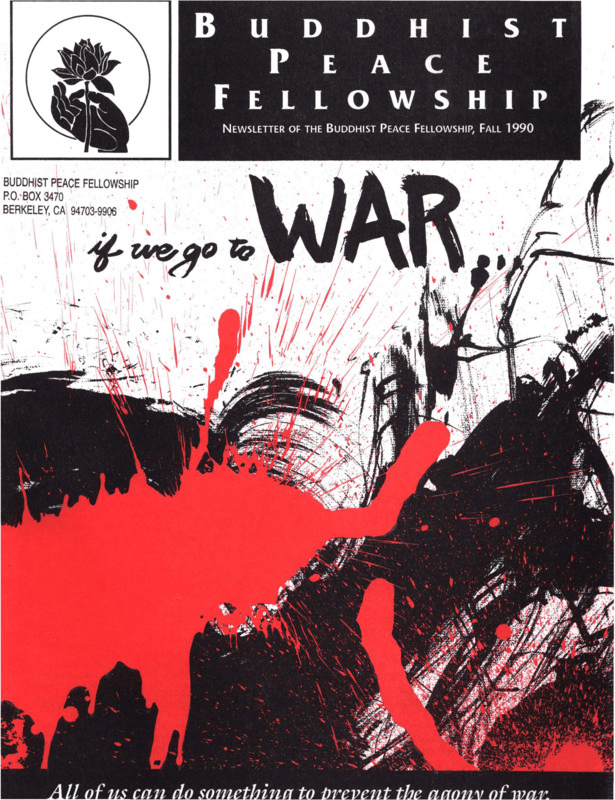

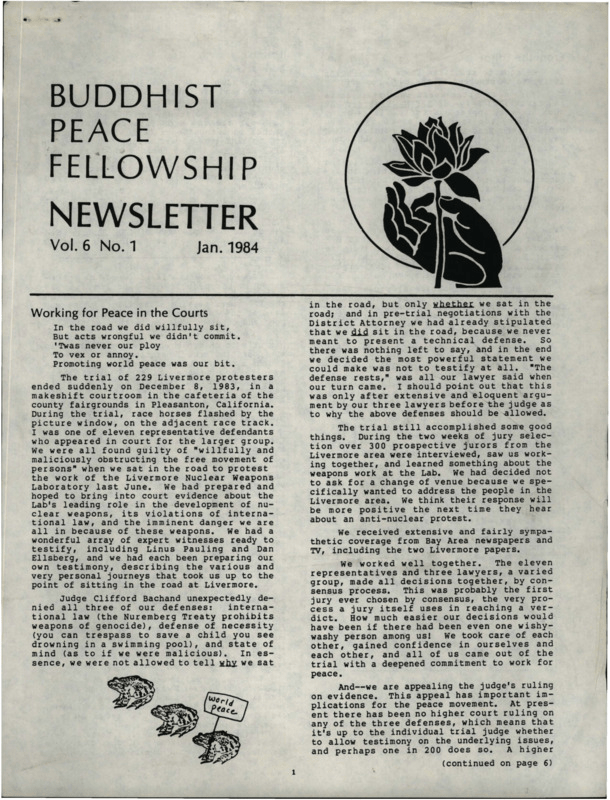

As the organization grew, members dove into a variety of issues: from anti-war and nuclear weapons, to prison dharma and human rights efforts in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Vietnam. In 1983, BPF and San Francisco Zen Center organized Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh’s first retreat for Western Buddhists. Hozan Alan Senauke strengthened ties overseas with the International Network of Engaged Buddhists, and Maylie Scott led BPFers in prayer sitting zazen on train tracks, blocking weapons shipments to Central America.

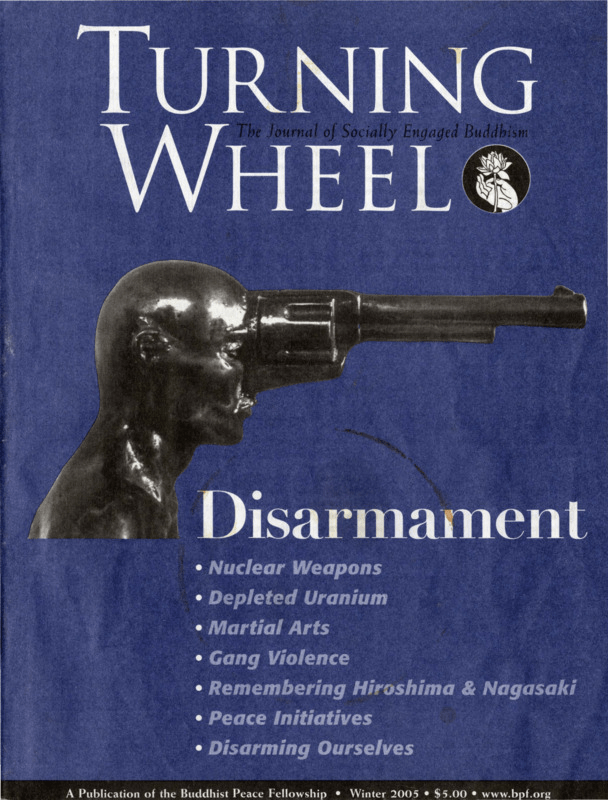

Turning Wheel, the official journal of the BPF, evolved out of the organization’s longstanding newsletter. It was published as Turning Wheel from 1991 to 2011. Both publications served as a forum for dispersed members to connect, share news and debate various points of theory and practice.

From the BPF website:

“From the beginning, BPF has had a newsletter. The first versions are typed and mimeographed, mailed to a small set of friends of the founders. As membership grew, the newsletter was the mail form of communication between socially engaged Buddhists. Early issues of the BPF newsletter featured pieces on Theravada, Tibetan, Zen, and Pure Land traditions, outlining a doctrinal and historical basis for engaged Buddhism, and setting precedents for our own emerging work. These foundations were important at a time when most Westerners turned to Buddhism as an escape from the world and the turmoil of the times.The quality of the newsletter continued to improve, and soon Turning Wheel evolved into an award-winning magazine in its own right. Under the editorship of Susan Moon some of the best known thinkers and writers in socially engaged Buddhism appeared in Turning Wheel’s pages: Thich Nhat Hanh, Joanna Macy, Gary Snyder, Alice Walker, and of course our founder, Robert Aitken Roshi.”

I was given access to a digital archive of Turning Wheel and the original BPF newsletter back in 2022. It is now available publicly at the University of Idaho digital collections website. While this archive doesn’t include every issue, it contains a substantial number of complete issues of the newsletters and the journal. By searching this archive I was able to trace a consistent thread of influence from anarchism and the revolutionary socialist left from the BPF’s inception until today. Importantly, this influence was not only among the founders: it appeared to have spread to younger generations of members as well. In the following, I will provide quotes, references, and anecdotes from every mention of anarchism I was able to find. Some of them may agree with this or that position that you and I like or dislike. In this context, I am not out to criticize, simply to document a trend. But before we dive in, some more context.

The political climate of the 1970’s set the stage for the BPF. The Vietnam War brought together counterculture activists and religious leaders from Asia and the United States, most notably Thich Nat Hanh’s rise to fame as an opponent of the war in exile. In Japan, Ichikawa Hakugen served as an elder and leader in the anti-war movement. It was at the start of this decade, in 1970, that he published his infamous book,, Buddhist War Responsibility (Bukkyosha No Senso Sekinin), criticising Japanese Buddhist support for imperialism, fascism and instigation of the Pacific War. Along with its meticulous documentation of Buddhist statements and actions in support of war, Ichikawa critiqued the underlying ideological weaknesses of Buddhism itself. From this critique he hoped to understand how Buddhists could have supported wartime atrocities and to discover ideological antidotes to these shortcomings. It was in this book that he articulated the possibility of “Buddhist-Anarchist-Communism” as the necessary remedy, only nine years after Gary Snyder’s 1961 “Buddhism and the Coming Revolution” article was first published in San Francisco. As far as I know, the two never met, but developed their ideas independently: Ichikawa from the pre-war Japanese anarchist movement; Snyder through the influence of his parents, longtime members of the radical Industrial Workers of the World union in the forest industries of America’s Pacific Northwest. Ichikawa’s influence, however, was eventually felt in the pages of the BPF newsletter’s first issue, when Brian Daizen Victoria, an American scholar and Zen priest living in Japan, submitted an article about Uchiyama Gudo, the High Treason Incident, and Zen collaboration in the Pacific War, all of which would eventually become his famous work, Zen at War (1997). According to Victoria, he was personally encouraged by Ichikawa to write this book, which builds on Ichikawa’s scholarship and criticism.

In the July 1979 BPF Newsletter, Paul Stammeier, a BPF member from Germany, wrote that was inspired by the anarchist pacifism of Gandhi, Kropotkin and [Gutsav] Landauer. Stammeier wrote that he was interested in a synthesis of libertarian socialism, buddhism, and Christian social gospel. In this same issue Brian Victoria submitted a column which mentioned anarchist martyr Uchiyama Gudo and the High Treason Incident in Japan.

The BPF Newsletter Vol 6, No 1, Jan, 1984 had a brief letter from the Rochester BPF chapter, which was, “taking on the resource project which aims to produce a collection of previously published but hard to find articles on the Buddhist rationale for peace and environmental work, right living, anarchism, deep ecology, nonviolence, and such movements as Sarvodaya.”

In the 1989 Summer newsletter Catherine Ingram interviewed Gary Snyder. Their discussion about anarchism and violence was very interesting. I have always appreciated Snyder’s refusal to ever completely rule out the need for defensive violence and revolution. Ingram asked Snyder, “You spoke at one time in “Buddhist Anarchism” about gentle violence being an acceptable response to stopping what is wrong. Then you modified that in a later interview to “You set yourself against something rather than flow with it,” and you spoke at that time about having to “karmically dirty” our hands to live in this world. How might people today say no to a wrong in a contemporary issue? How would you “set yourself against it?”

Snyder replied, “Well, it depends on the nature of the wrong and it also depends on how close it is to you. Things that are dumped in your lap, things that come up to your front door, you are really karmically obligated to deal with, I do believe. Poverty, oppression, rank injustice right in front of you is yours…Nonviolence is always the way, but you can’t always do it. That’s what it comes down to. Non-violence is always the way and if you can’t always do it, you don’t talk about it.” I feel like that last line is going to stick with me for a while. If you can’t always do it, don’t talk about it.

In the Fall 1991 issue, BPF founder Robert Aitken Roshi wrote an article called, “Engaged Anarchism” which talks about committing free time to political action. It references the Catholic Workers movement extensively. Aitken and many others have looked to the Catholic Workers as a model of a religious organization engaged in anarchist politics, primarily through charitable works and anti-war organizing. It seems that Catholic Workers were a major source of inspiration for the BPF, both in structure and in spirit.

Anne Herbert, an author and editor of the journal CoEvolution Quarterly, which was a precursor to the countercultural touchstone “Whole Earth Catalogue”, described herself as a non-violent anarchist for a column in the Winter, 1995 issue.

In the Fall 1997 issue, Susan Phillips wrote a review of the prison documentary “Voices from the Inside”. Her author bio read: “Susan Phillips lives in Philadelphia and is active in the prison rights movement. As an anti-death penalty activist and member of the Philadelphia Anarchist Black Cross, she is currently producing a video on one of the groups she is active with called Books Through Bars, which provides books and educational materials to indigent prisoners.”

In the Spring 1998 issue, Donald Rothberg reviewed “Entering the Realm of Reality: Towards Dhammic Societies” (edited by Jonathan Watts, Alan Senauke and Santarikko Bikkhu) and offered a critical perspective: “Is there some kind of natural affinity between Buddhism and modern and (usually) Western Green, anarchist, decentralist, anti-capitalist, and socialist approaches, as is implied by many of the authors, despite the fact that Buddhism has also historically sometimes been harnessed to nationalist and right-wing approaches, notably in Japan in this century?” Simon Zadek, on a more cautionary note, criticized fallacious arguments in favor of radical syncretism: “I am a Buddhist and think this way about social issues. Therefore, this way of thinking is Buddhist.” Both, in my opinion, are important to keep in mind when contemplating this topic.

In the Fall 2002 Turning Wheel (now upgraded from newsletter to magazine/journal) the artist Canyon Sam wrote “A Journey of Politics, Art, and Spirit” and mentions that “Looking back, I find it odd (or perhaps destiny) that I became who I am today. When I was nineteen, I came out as a radical lesbian feminist and socialist anarchist.” In the same issue, the article “Passionate About Liberation”, an interview with five young engaged Buddhists, included this response from a member named Steven: “I’m 21. I’m from Long Island, New York. I guess I’m bicoastal now. I’m spending time on the East Coast right now, but I live primarily in Berkeley, California. Throughout my childhood and growing up I pretty much maintained the same core values of truth and justice and curiosity and creativity. At the same time that those ideals were ripening, I found myself falling into anarchism, activism, and Buddhism, and they were all connected for me.”

Another 2003 Turning Wheel article in the Winter issue mentioned a Nipponzan Myohoji nun named Jun Yasuda, famed for her numerous peace walks across the United States, particularly in solidarity with Native American movements. In a 2017 interview Yasuda remarked that “I studied Buddhism watching native people,” The Turning Wheel article mentioned that Yasuda originally left home at 16 due to conflicts between her family and her interest in “radical anarchist activism” before joining the Nichiren-inspired Myohoji sect. She still leads peace walks across the country, including in support of movements against fossil fuel expansion.

The Summer 2005 issue of Turning Wheel included, “The Spaces Between” by Katherine Lo. In the article Lo compares anarchy to various spiritually ultimate, absolute or inexpressable truths, “Our face before our parents were born could be Buddha-nature, or anarchy, or the Dao, or whatever word-symbol we have forced onto something that is, in the end, wordless in its deafening proclamation.”

The Fall 2005 Turning Wheel, in the section called “BASE News” included this report from Justine Dawson: “I traveled to the Bay Area, excited to meet what I imagined would be my comrades in BASE: anarchist Buddhists, simple-living yogis, and communally minded monks. I was ready to be held and supported in a community of like-minded radicals who might nurture my skills and social views. What a surprise it was instead to be greeted by a much less predictable collection of fellow seekers: homemakers, journalists, students, and businessmen, to name a few. My vision of social change began its slow evolution…I soon became aware that the world of engaged Buddhism was far more nuanced and complex. When my mentor said, ‘Someone had to parent Thich Nhat Hanh’ I suddenly understood what it was all about.” BASE refers to the BPF’s attempt to build up anarchistic communes of members. These can be understood as something like a hybrid religious community revolutionary affinity group. Aitken and the unofficial “anarchist caucus” of BPF were very keen on these as a model for the locals of the organization. Alan Senauke wrote that “Diana Winston, Donald Rothberg, Maylie Scott, and I spent long hours together in the mid ’90s developing a BASE model and fine-tuning the first groups.”

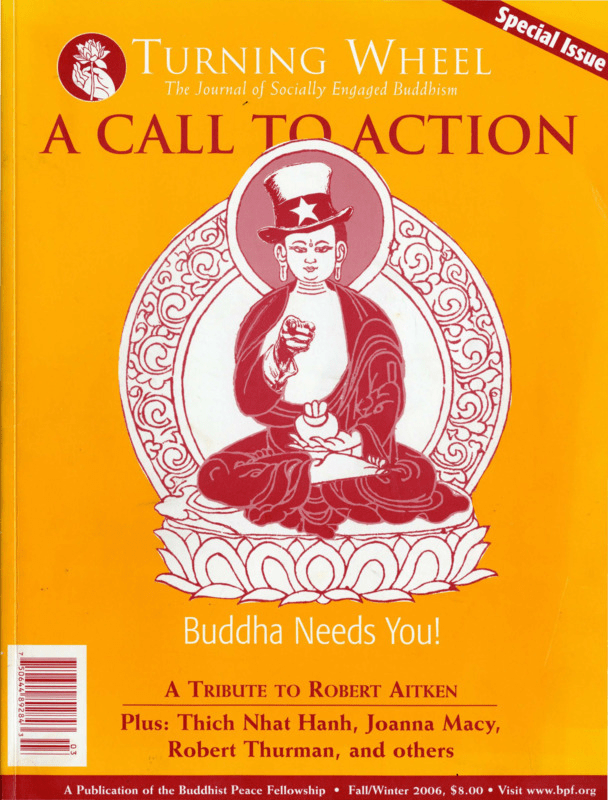

The Fall 2006 issue was rich with anarchist references. The issue opened with “Taking Responsibility”, a transcript of the talk given by Aitken Roshi, quoted at the start of this article. Another article by Aitken Roshi, “The Groundless Ground of Social Action” by R. Aitken utilizes the “Three Bodies of the Buddha” (Trikaya) theory to walk the reader through a spiritual-social critique of reality and the seemingly intractable nature of war and human stupidity. The Trikaya are views of the same reality, from a perspective of universally clear totality (Dharmakaya), luminous, interdependent spiritual grandeur (Sambhogakaya) and the miraculously tender appearance of everyday life (Nirmanakaya).

“Get these terms straight. The Dharmakaya is the total absence of any enduring self. You and I as poets realize we have no identity. We have no future. This is it! You are not reborn in any kind of next world. Where did the Buddha talk about eternal paradise? If he did, he contradicted himself, or the sutra is spurious. Knowing that our fellow beings will die soon, and that their death is forever, can only evoke compassion, suffering with them, pecking about in the gravel with them.”

“The Sambhogakaya is the containment of all beings and things by all beings and things. “I am large; I contain multitudes:’ Indeed. Keats took part in the existence of the sparrow, while the perversion of this realization would be schizophrenics, who find all arrows of their sociograms pointed to themselves. It would be the CEO who uses all beings for himself or herself. Contrast with the noble person whose arrows point in all directions and who is used by all beings, keeping healthy and educated for that purpose.”

“The Nirmanakaya is the infinitely precious nature of all beings and things, including sparrows.” In this paragraph, he mentions Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution as an example of the tender kindness to be found even in a seemingly cold and hostile nature.

“The groundless ground of social action is the ground of making one’s bed and brushing one’s teeth, of course, but that is another story. Let’s concern ourselves with social action. It is a pressing concern today.”

“The Buddha did not avoid politics any more than Jesus was meek and mild. It is surely past time we turn the criminals out, but we can’t do that with rhetoric. With worthies of the past looking over our shoulders, let us conspire. Let us breathe together and make it happen, and conspire to keep it happening.”

“Another Aitken Legacy: His Political Library” by Chris Wilson mentions Aitken’s influences in Marxism, anarchism and more, in reference to the extensive personal library he donated to the BPF headquarters. Wilson write that, in particular, “Peter Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid, a book that Aitken has cited in his essays, perhaps best reveals the nature of his interest in anarchism. A nonviolent and antimilitarist anarchist, Kropotkin was a brilliant Russian prince who was disowned by his family for his progressive views. ( One could even say that he “left home” like an earlier prince.) He became world famous for his geographical and zoological studies in Siberia in the late 19th century. He was an early supporter of Darwin’s theory of evolution but a bitter opponent of certain populizers of Darwin ( e.g., T. H. Huxley and Herbert Spencer), who used “survival of the fittest” as a rationale for predatory capitalism and imperialism. Kropotkin wrote Mutual Aid to answer Huxley and Spencer, arguing that all societies showed more cooperation than conflict. By documenting the tendency toward mutual aid in both animal societies and human cultures, he argued that the natural course of evolution was toward greater cooperation, not greater competition. Because of his emphasis on the interdependence of all life, Kropotkin is now widely regarded as a founder of ecology.

Aitken clearly favors Kropotkin’s conclusion that human society will evolve to a point where voluntary coalitions will become the prevailing political form for peacefully resolving problems. Aitken has long argued that communities of Buddhist activists may become models for a general social transformation (see Aitken’s essay “Envisioning the Future” in his collection Original Dwelling Place). Aitken’s political books imply that change will come not through a universal conversion to Buddhism but through all peoples grasping the interdependence of all life, a change of consciousness that Buddhists will help to bring about.“

“Anarcho-Buddhism and Direct Action” by Matthew S. Williams: critiques individualist approaches to structural problems. He specifically calls out people’s inability to see systems as evil entities; individuals’ are not so much causal agents, but cogs in a machine beyond any one person’s control. For example, blaming President Bush and not the government as a whole for the Iraq War, as well as the engaged Buddhists who “focus solely on compassionate dialogue with evildoers in power, failing to see how the social structure blocks the possibilities for such dialogue.” He concludes that, “To get to the root causes of social injustice, we need a radical social analysis that helps us understand how social structures shape people, one that looks at both individuals and the larger social context in which they act, and at the interdependent origination of self and society“, and that, “What we must oppose is systematically institutionalized ignorance, not the individuals caught up in the system who suffer from their own unwholesome emotions and false perceptions.“

“In-your-face Dharma” by Maia Duerr has this quote from Aitken: “I felt most honored to experience the dharma talk on Friday night by Robert Aitken Roshi, who turned 89 years old that same weekend. A highlight for many of us was his dharma advice to do something drastic-we should be getting naked in the streets! [Roshi invoked the Doukhobors, a pacifist Christian sect that originated in 18th-century Russia. The group participated in mass nudity and burning of weapons in protest against militarism and materialism.] In his talk, Aitken Roshi spoke with respect of Christian anarchist and peace activist Phil Berrigan. Someone in the audience asked Roshi for his thoughts about tax resistance and other acts of civil disobedience. Roshi told us to consider others who are involved in our lives. He noted that it was a hardship for Phil Berrigan’s children that he was in prison for many years. I heard in that a keen understanding of the Middle Way. We must speak, we must act, we must put our naked selves on the line for the good of the world, but in doing so we must consider our loved ones and all who could be affected by our actions.”

TW Spring 2007 has this letter from Gary Hallford, an inmate of Vacaville Prison, in response to “A Call to Action”, published in Turning Wheel Fall/Winter 2006: “How do we bring about any positive changes in a severely corrupted society? There are never any easy answers. Yet Mr. Aitken is accurate when he states that Buddhists are anarchists. Failure to recognize that truth defies the dharma and unnecessarily complicates our lives and our societal connections.“

A Summer, 2008 article by Alan Senauke and Donald Rothberg mentioned Aitken Roshi’s anarchism: “Aitken’s study of anarchist writing-Proudhon,Kropotkin, Landauer, Emma Goldman, and many others-reinforced his belief in personal autonomy, decentralization, and spiritual community. These are principles that are also the essence of Buddhist Sangha, as he has written: The traditional Sangha serves as a model for enterprise in this vision. A like-minded group of five can be a Sangha. It can grow to a modest size, split into autonomous groups and then network. As autonomous lay Buddhist associations, these little communities will not be Sanghas in the classical sense, but will be inheritors of the name and of many of the original intentions. They will also be inheritors of the Base Community movements in Latin America and the Philippines: Catholic networks that are inspired by traditional religion and also by 19th-century anarchism […] Local BPF chapters still function with great autonomy, bound by their mutual practice. This web of sanghas is a small step in the direction of what Aitken calls Buddhist Anarchism, which itself is a small step towards the healthy remaking of society. Aitken frequently cites the old Wobbly (Industrial Workers of the World) motto: “Build the new within the shell of the old.”

In the same issue, the article “Zoom Out, Drill Down, Help Someone” by C. Wilson mentions several anarchist principles at work within the BPF’s founding organizational strategy: “The reliance on local chapters for BPF’s peacework is the result of a long-standing policy that the national staff does not prescribe strategy for the chapters, in keeping with the nonviolent anarchist principles of founders and supporters such as Aitken, Foster, Snyder, and former BPF Executive Director Hozan Alan Senauke.”

What we can conclude from this study is that anarchism was deeply ingrained into the organizational ethic and structure of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship. At times it was more or less pacifist in rhetoric, but certainly never passive. The BPF was deeply involved in and shaped by the anti-war movement of the 1970’s into the Iraq War. It seems that as the mainstream anti-war movement declined, so did the BPF’s base. This is a common problem for anarchist organizations which are strongly tied to a particular social movement. When their “social vector” dies out, so do they. Thankfully the BPF still exists, though in a smaller, non-profitized form, and mostly focuses on educational events and trainings. Today there is a new anti-war movement, primarily in support of Palestine, and lately, against US intervantion in Venezuela, as well as numerous movements, from unionism, tenant organizing and fights against immigration enforcement operations in the US. The legacy of anarchism in the Buddhist Peace Fellowship demonstrates that when we choose to organize ourselves as an active minority and intervene, it makes a difference. Not only for the goals of these movements, but for the militant religionists who make a stand. Many of the BPF members featured here had long careers and must have taken their political experiences with them. This likely had impacts that mere scholarship will be unable to uncover.

I think that if we are to take any lessons from anarchism in the BPF, it would be the importance of community. I started this blog because I felt isolated and alone in my political-religious beliefs. Having a political home, a “BASE”, to roots oneself in provides stability in the midst of struggle and turmoil. If I were to offer a critique of the BPF’s BASE model, it is that it focused too much on activism to ever take root as a viable social and economic alternative for everyday people. It seems Aitken was well aware of the issue, particularly free time. In the 1991 article “Engaged Anarchism” he talked about the difficulties ordinary people face just getting time to visit the zendo, let alone attend a protest, “So I suggest that we, in our Buddhist Peace Fellowship groups, be aware of ourselves as base communities, coming together for mutual support, meditation, planning, and for action. And I don’t necessarily mean putting ourselves on the line – although that’s important too, as it was during the Persian Gulf War. You know, we can form our own small instruments of power. I like the idea of little credit unions, little markets. But it takes a lot of work, a lot of relinquishment.”

Communitarianism today seems like an idea which has come and gone. You either sparate yourself from society in a community that eventually collapses. Or you collapse under the weight of balancing everyday life, a job, drama, etc, with your part-time volunteer job at the food co-op or whatever it is you’re passionate about. As one Turning Wheel contributor quipped, “Is “community” being sought in a spirit similar to the longing for consumer goods?”

Small changes sometimes just stay small and burn through people until they either conform or fizzle out. Resistance is futile, it seems. But the promise of the coming community cannot be dismissed so easily, no matter its past failures.

As economic and social conditions worsen, it is not just hippies and meditating Buddhist activists who will need a community to take refuge in. Building practical communes of refuge and survival, where maybe the members are neighbors in the same building who simply share grocery expenses, childcare duties, home repair and transportation costs might be a simpler and more sustainable goal. Only when working class people have our basic needs for time, money, food, clothing and shelter met can we start to think about improvement through political or spiritual practice. There is no way in hell many of us could work any harder without dropping dead. But we can make the best use of our meager resources by combining them and managing them collectively. Buddhism in America has typically been a middle class phenomenon. What might it look like to build a refuge for the rest of us?