“The bodhisattva practices emptiness, but he does not realize emptiness…He considers peacefulness but does not seek extreme peace.”

– Vimalakirti Sutra

By way of (re)introduction

Hello, my patient readers. Believe it or not, the work continues behind the scenes. It took me some time to come back around, but I am back on this project for the foreseeable future. I feel that this hiatus has been good for me and for this work.

So why start with ancient Chinese peasant uprisings? I’m not entirely sure myself. It was just another historical footnote which I had skimmed over in earlier research. On a whim I decided to look into it more closely. I found a lot more than I expected to. The history itself is incredibly interesting. Engaging with it has also broadened my horizin of what might be possible to put into practice. This will be an incomplete history essay interspersed with commentary and digressions. For a more accurate and chronological history please refer to the sources listed at the end of the essay. I recommend starting with the “History of China Podcast” episodes on the Red Turban Rebellion. I was first clued in to the existence of messianic Buddhist rebels by the Vietnamese libertarian communist Ngo Van in his 2004 essay “Ancient Utopia and Peasant Revolts in China”. He left me with this incredibly enigmatic paragraph (and no citations):

“In 1120, in Zhejiang, the special taxes levied to pay for the construction of the Imperial Palace at Kaifeng provoked a brief uprising led by a Buddhist secret society influenced by the spirit of subversive Taoism. The rebels, poorly armed, strict vegetarians who worshipped demons, massacred the rich, government officials and dignitaries. When its leader Fang La was captured after a year of fighting, the rebels escaped the repression that was in store for them by means of collective suicide.”

Demon-worshipping vegetarian Buddhists waging violent class war, you say? An anecdote like this goes against almost everything modern Buddhism defines itself as. How could it possibly be true?

As it turns out, this particular story is mostly apocryphal (Fa Lang, though a real rebel leader, was probably not a demon-worshipping class warrior. Today he is best remembered as an antagonist in the 14th century Chinese novel, Water Margin). But like most classics it is based on a true story. There was indeed an ancient Buddhist-Taoist secret society of rebellious heretics who instigated countless uprisings from the undercurrents of Chinese history. Or rather, there were several. This is an attempt to understand their history and draw out lines of flight which may inspire modern, more coherent heresies.

The idea of religious violence, much less popular revolutionary violence, is anathema to the narrative of modern Buddhism. If there is one thing you are not allowed to advocate in Buddhist circles it is violence: no qualifications, no nuance, go straight to hell. But this aversion to the mere mention of violence has more to do with modern social conditions and the selective reading of Buddhist literature by modern western subjects than it does Buddhism itself. Through this research I have been able to gradually peel away the layers of liberal ideology which have incubated this pacifying fiction. Just as much as modern Buddhists need to be confronted with the problematic history of reactionary and dominating violence in Buddhism, we need to learn about its hidden history as a tool of the oppressed. To explore this possibility is the supreme of heresy of modern Buddhism.

Glenn Wallis, author of the pamphlet, “Heresy: A Non-Buddhist Guide”, defines a heretic as a “devoted practitioner whom the authorities of their tradition deem dangerous… A heretic, in short, remains committed, albeit in a complicated way, to their tradition and, crucially, takes on the responsibility for transforming it.” In the vocabulary we have been developing for this project, heresy is none other than the very practice of freedom-emptiness which our “tradition” militates for. Heresy, Wallis points out, comes from the Greek hairetikos, meaning “to be able to choose; the be able to have a distinct opinion.” For our opinions to be meaningfully distinct, however heretical they may be, they still have to be in dialogue with reality. In order to ground this exploration I would like to briefly direct the conversation back to methodology.

Heretic historiography

Since returning from hiatus, among other things, I have been interested in revisiting the pre-modern historical roots of Buddhist Anarchism. This is because I have clarified my historiographical methods. Instead of searching for analogues of Anarchism in the distant past long before it was developed I will look for its ancestors. This helps us avoid anachronism and the pitfalls of projecting modern ideologies onto the people of the past. Anarchism is by definition a movement which was born from the struggles of the industrial and agricultural working classes in the context of industrial capitalism. It is one member of a family of radically egalitarian ideologies born in this same context which can broadly be categorized as “socialist”.

The historiographical method I have arrived at is inspired by “An Historiography of Anarchism”, a chapter from the book Bandeira Negra by Felipe Corrêa. “An Historiography” criticizes previous theories of anarchist history and proposes a new method based on historical data and clear criteria. While the result is a powerful analytic tool for understanding anarchist history, the precision of this method has to be modified for our purposes. Rather than a well-defined current of self-identifying revolutionary action such as anarchism, we are stitching together a story in order to discover a new or emergent tradition.

There is a sense among some people that the Buddhism and Anarchism share a natural affinity. Without knowing why, it just feels like a good fit. The purpose of this historical research is to better understand why this feeling arises for some people and what it is about these currents of thought that they are actually identifying. Humans, like many animals, make use of binocular vision to visually perceive space as “depth”. Like two integrated views from two eyes, I suspect that the picture of “depth” that we are identifying only emerges when the two views of Buddhism and Anarchism are able to see themselves through the perspective of the other. An integrating view of Buddhism and Anarchism, like depth-perception, requires us to move in and out of focus. To examine in detail some aspects, others must become blurred as they shift into the background or peripheral field of knowledge. My main critique of previous attempts at Buddhist-Anarchist synthesis is that they focus on only one layer of Correa’s historiographical categories and are thus unable to perceive the whole problem space. The object which we are unearthing is three-dimensional. Without, space, without depth, without emptiness, no movement, and thus no understanding, is possible.

The first and most common lens I see people apply to this topic is that of philosophy. While in a sense entirely understandable, and even necessary, (these are, after all, ideas we are working with) it does not allow space for practice to emerge in dialogue with theory. Superficial philosophical analyses make analogies between a favored political ideology and cherry-picked elements of a religious ideology (“Doctrinal examples x, y, and z support my interpretation as the most correct interpretation… but only if we ignore or deny examples to the contrary a, b, and c)”. A review of the literature shows that this can be done for almost any imaginable combination of political and religious ideas. Synthesis of Buddhism, anarchism and socialism are by no means unique in this respect. By this standard something as evil Buddhist fascism could be equally coherent with enough selective reading and interpretation (and in fact Japanese Buddhists did exactly this during the Meiji era of imperial expansion). This is not to say that synthesizing ideas from different domains is wrong. But we risk attaching ourselves to inanimate ideological fixations with no connection to reality. The connections which are made are not organic. They did not develop in dialogue with particular people or contexts beyond the author’s own biases. The only way to breathe life into such laboratory creations is to subject them to critique.

So as a critique of abstract philosophical speculation we can look at history. There we can find similar themes of liberty and equality from other eras and can erroneously conclude, “a current of anarchism has existed in all cultures since prehistoric times”. But despite superficial similarities there are always real differences between people and events from the distant past. What’s worse, we risk obscuring the lessons we might learn by lumping everything together into the category “anarchism”. This also distorts the boundaries of anarchism to the extent that it becomes difficult to define or use. Corrêa writes, “By defending the timeless universality of anarchism, this approach gave rise to a “legitimizing myth,” a “metahistory” that, consciously or unconsciously, sought to strengthen its own ideology by refuting the notion that anarchism is incompatible with human nature. However, I argue that anarchism does have a history, one intimately related to a particular context. Its emergence and development, successes and failures, ebbs and flows, can only be understood and explained in historical terms. It’s essential to make use of an historical method and to develop a robust relationship between theory and history. For this reason, ahistorical approaches to anarchism should be abandoned.”

So we have to be more specific. To be specific is to measure our hypotheses against a context, i.e. history. Biography is one of the most direct ways to do this. The documentation of a person’s life and ideas provides a window into the past. For the most part this is what I have had to do to stitch together this history. There not being a distinct “Anarchist/Buddhist” movement with sources to draw upon, we have to understand this current through the lives of individuals. Still there are problems here as well we must be aware of.

As we know, people’s identities are not always stable throughout their lives. When we have the luxury of looking at their whole story, some of their actions can be confusing and contradictory. Many of the people I wrote about in previous historical overviews such as Taixu or Har Dayal were only involved in anarchism for a short period of their lives before de-radicalizing in middle age. This is understandable, but only if we accept that these people weren’t anarchist superheroes or “Great Men”. Is it really so surprising that they renounced revolutionary militancy after they saw their comrades slaughtered and their projects destroyed? Most readers of this blog are probably familiar with the phenomenon of activist burnout. Why should we judge the people of the past by a higher standard? According to Corrêa, “Historiographic methodology has tended to focus on “great men,” producing what could be called ‘histories from above.’ Frequently, the ‘history of anarchism’ boils down to biographies of the lives of these “great men,” or to descriptions of their ideas and theoretical conceptions, without accounting for historical context, the practices of popular movements, or the diffusion and historical influence of actions and ideasBecause real “Men” aren’t ever “Great”, history can occur. Despite our imperfections, we can really only judge actions on the level of collectives and movements.

But lacking a coherent “movement” to contextualize or large datasets to work with we must attempt to synthesize biography with whatever available contextual information we can find. Doing so sets up a dynamic relationship between the individual, society and ideas in history. If, as Buddhists claim to do, we understand the “self” as a socially constructed emergent entity without an underlying “essential” reality (anatman), the picture of an “interdependently arisen” (pratītyasamutpāda) history comes into view, where the individual in time reflects and influences the social, historical and natural relationships which have formed it.

Three currents, one river

However, we can not tell a useful story with an interdependent history of everything. What I have found works well enough and have attempted to maintain is a sort of dynamic movement between ideas, people and contexts which makes an attempt at “connecting the dots”. For me anarchism is a phenomena originating in the socialist movement of the late 19th century which has continued until today. It is a particular manifestation of the older, trans-historical currents of liberty, equality and revolution.

Anarchism distinguishes itself from other socialist currents by its insistence on liberty and revolutionary change as indispensable means to the common socialist goal of political and economic equality. In practice this results in strategies of opposition to state power and hierarchies of interpersonal domination. It counterposes a defense of democratic self-managing social movements as the protagonists of revolution. As Bakunin famously wrote, “ We are convinced that liberty without socialism is privilege, injustice; and that socialism without liberty is slavery and brutality.” Liberty then, for the anarchist, must also be distinguished from mere individualism, because “The freedom of all is essential to my freedom.” Freedom is an interdependent and social phenomenon.

The pre-modern historical record may be devoid of true anarchists but it is not hard to find evidence of egalitarianism, libertarianism and revolution. These traits seem to be more or less innate to the human social-behavioral spectrum, and as such appear in nearly every time, culture and place to varying degrees. Anarchism is one of many expressions of these currents.

People and movements which share some of these ideas could be said to be the “ancestors” or “headwaters” of anarchism. Helpfully, this “confluence” method clearly points out the fundamental point of unity between Buddhism, Anarchism and other movements towards liberation: the idea, practice and realization of freedom. These are movements which, at some point in their histories, have recognized that freedom is possible and attainable by taking methodical, self-conscious and collective action. Its necessary features are equality, liberty, fraternity and the revolutionary abolition of all systems of domination. Importantly, the river formed at the confluence of these currents is not a static entity. It is said that one never steps foot in the same river twice. It also ought to be said that the same person never steps foot in any river twice either. It follows that the same applies to Buddhism, anarchism and any other ideas people may encounter in the incessant flow of history. It is with a flexible, pragmatic and open view that we must approach these topics.

Undercurrents of egalitarianism and libertarianism are well documented in the history of Buddhism. But revolution, is, we are told, all but nonexistent. This is not all that surprising. Buddhism as a practice promoted detachment from society. As an institutionalized religion it relied heavily on patronage from the rich and powerful. Doctrinally Buddhism centers non-violence as a core practice. Simply reading the sutras and commentaries would not give one the impression that Buddhists could ever practice political violence. But this is emphatically not the case.

From insight to insurrection

The ancient world was a rather violent place, at least if you happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time (like Yuan dynasty China, as we will see). Buddhist sects and leaders regularly used violence: for self-defense, for political advantage, for expropriation and for conquest. Temples would often form militias and even field armies in the service of feudal lords. We will find that this story is intimately connected to the history of the East Asian martial arts. The famous Shaolin kung-fu was invented by Ch’an monks for self-defense against bandits and warlords; in the case of Wing Chun boxing, the legend says, it was invented by a Buddhist nun for women to defend themselves from men. Monks would often crop up as leaders or instigators of peasant uprisings. But the vast majority of Buddhist institutions enthusiastically used or support violence in support of the status quo. Its function was to quell rather than to instigate popular discontent.

It seems that for Buddhism to become an insurrectionary motive force it needed to evolve. These could only evolve under the influence of the right environmental pressures. First and foremost, to foment rebellion Buddhism needed to get less intellectual and make its practices available to the illiterate laity. Sects which emphasized devotional practices were the most likely to develop the mass base of support required for popular power. For a devotional Buddhism to become radicalized against the ruling class it also needed a narrative of conflict which spoke to the injustices and challenges ordinary people experienced. What’s more, they required an immanent, worldly paradise for which the battle would be waged. Revolutionary dramas require protagonists to drive the plot forward. In this case, the faithful believers of the prophetic vision saw themselves as protagonists in a cosmic war between the darkness and the light.

Manicheanism was a syncretic religion originating in Persia, taught that the universe was defined by a conflict between the forces of good/light and evil/darkness. It drew upon the doctrines of Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Judaism, Islam and Christianity. Its believers saw themselves as partisans of this struggle and spread their doctrine across ancient Eurasia, East and West. When it arrived in China it fused itself to pre-existing peasant beliefs in Animism, Taoism and Buddhism. It’s militant attitude added the spark of conflict and spiritual utopia which Buddhism lacked, turning the smoldering embers of peasant resentment into the sparks of a blazing prairie fire.

To further radicalize and identify themselves as revolutionary subjects, popular Buddhist sects distinguished themselves from the mainstream by adopting “countercultural” lifestyles, practices, rituals and identifiers. Vegetarianism, for example, was often associated with the Chinese heretical sects of Buddhism.

The actual practices of a counterculture are often unimportant in the eyes of the mainstream. B. J. Ter Haar writes in “The White Lotus Tradition in Chinese Religious History” that, “From the Song onwards, three phrases recur frequently in connection with religious heterodoxy: ‘gathering at night and dispersing at dawn'(yeju xiaosan), ‘men and women intermingling indiscriminately’ (nannu hunza), and ‘eating vegetables and serving the devils’ (chikai shimo)”. These, Haar says, were more often labels applied to religious heretics in general, and were “stereotypes used to disparage, rather than describe religious phenomena.” Other Buddhist critics of heretical lay Buddhism accused them of practicing Taoist internal alchemy and sexual yoga. In general, they were disparaged as lowly and crude religionists who gathered at night because they needed to go to work during the day and were generally suspicious if not openly seditious.

For active sedition to overtake clandestine counterculture, popular sects needed to encounter significant political instability. Foreign invasions, plagues, famines, floods, civil wars, unfair tax structures were all agitated the people against the government. They also drove people into the arms of cults who preached that “the end is nigh”. To risk it all on rebellion people needed to really feel like they were living in the end times. The 14th Century was just such a time. A massive climatic shift towards colder and drier average temperatures destabilized crop yields and promoted the spread of diseases like Bubonic Plague. Winters were longer and colder. Rivers alternately dried up and flooded. Hunger and tax deficits led to banditry, piracy, exploitation and civil conflicts, all of which fed back into less reliable food and more political unrest. This was a time of global instability, and East Asia was no exception. In fact, as the History of China Podcast points out, China had an exceptionally unlucky 14th Century. Most civilizations of the time could and did withstand one or two concurrent calamities brought about by climate change. It would take more than a few disasters to break down a reasonably stable government. Yuan China was unfortunate enough to experience all of these within a very short period of time during the rule of an incompetent and widely hated foreign emperor. For the average person in 14th Century China, the end wasn’t just coming. It was here.

To complete its evolution into a revolutionary doctrine, the sect needed to respond to the apocalyptic conditions the people lived with. Yes, the world is ending, they said. But this is actually a good thing: the destruction of this corrupt and sinful world heralds the arrival of heaven on Earth. This phenomenon, called millenarianism, is found in nearly all religions. Its common features are a belief in an impending calamity, a prophet or savior come to liberate the chosen believers, and most importantly, a belief that a utopia was coming as surely and as swiftly as the dawn. In this utopia, the existing order and institutions of the world would be turned upside down. In the ancient world Millenarian cults were one of the primary outlets for the common people to express their class anger.

Buddhism has its own history of millenarianism, particularly well-documented in Imperial China. It is almost always tied to prophesies of the future Buddha, Maitreya, coming to Earth and ushering in a new golden age of peace, prosperity and wisdom where everyone could easily attain enlightenment.

The doctrinal impetus for Maitreyanism to proliferate was the development of Pure Land Buddhism. This sect preaches that recitation of the names of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas was the most effective means of salvation. Because the world is in an age of decline, the Pure Land school said, the old methods of liberation are no longer available. People’s intellectual capacity has declined too far to understand the teachings. The world is too corrupt to practice virtue. Life is too short and unpredictable to spend years meditating in a cave. There were crops to be brought in, wares to be sold, disasters to endure, wars to be fought. Luckily, devotion to an archetypal, god-like Buddha will guarantee that after death the believer would be reborn in a heavenly Pure Land, no matter their intellect or capacity for religious cultivation. There, no one would suffer poverty, illness, hunger or oppression. All would have their needs met and be able to practice the true Dharma. Pure Land theory contains its own depth and complexity, available to the well-educated monks. But the bare simplicity of devotional Buddha name recitation made its promise of salvation from oppression and misery immediately available to the poor and illiterate masses of peasants, merchants, soldiers and craftspeople of China.

Pure Land beliefs on their own were not threatening to the worldly authorities. If equality only came after death, then the peasants could wait and pray for freedom while the worthy accumulated wealth and power in the here and now. But when the Buddha the people devoted themselves threatened to bring this utopian land to Earth, the rulers became concerned.

Lotus in a sea of fire

The White Lotus Society is said to have been founded by Huiyuan, the first Master of Pure Land Buddhism in China, in the early 5th Century C.E, as an association of his most accomplished lay followers. Because their teachings were practical, easy to understand and easy to propagate, the White Lotus Societies spread widely across China for several hundred years. At times they came into favor and were patronized by the government and the rich. At these times they used their wealth to sponsor public works and charities. In prosperous times like these the White Lotus Societies were seen as normal religious institutions run by laypeople. At other times they were repressed by hostile governments and had to practice in secret. Unable to meet aboveground, their doctrines began to diverge from the official orthodoxies. Clandestine, and rooted among the common people they fused with other religions, supported an underground system of mutual aid and secretly taught the peasantry medicinal, martial and magical arts with which to defend and heal themselves. Hated by the state and the religious authorities, the White Lotus sects were something like a cross between a revolutionary organization and a New Age cult.

While critical of religion as a potential “opiate of the masses”, social historians like Marx also recognized that in ancient imperial and feudal societies, religion may be the only available vehicle to inspire and unite the rebellious will of a people. In these cases, heresy can become a stimulant (or psychedelic) of the masses. It can heal people who are suffering. It can wake people up to reality.

Elizabeth J. Perry writes that, “Orthodox Neo-Confucians of the Ming and Qing periods were acutely aware of the intimate connection between folk religion and peasant uprisings. Thus such teachings and related organizations were outlawed by repeated imperial edicts.”

According to Theresa Flower, “The Great Qing Legal Code, which was in effect until 1912, contained the following section:

‘[A]ll societies calling themselves at random White Lotus, communities of the Buddha Maitreya, or the Mingtsung religion (Manichaeans), or the school of the White Cloud, etc., together with all who carry out deviant and heretical practices, or who in secret places have prints and images, gather the people by burning incense, meeting at night and dispersing by day, thus stirring up and misleading people under the pretext of cultivating virtue, shall be sentenced.”

Almost everything we know about the White Lotus comes from the records of their opponents in the government. The actual sects, probably due at least as much to sectarian rivalry as to a fear of repression, almost never referred to themselves as White Lotus. Furthermore the term White Lotus did not refer to any singular, cohesive organization as much as an ideology or loose collection of popular practices and beliefs which subverted religious and state orthodoxies. Many of the stereotypes ascribed to them were in fact part of the state’s narrative of a singular, widespread and powerful conspiracy of demon-worshipping, gender-mixing, vegetarian heretics. Chao Ch’ang-Shen, a government official who wrote an investigatory report on White Lotus ideology in 1769 called them “heretics of the left” (what exactly he meant by “left” in 1769 is unclear) who “gather people under false pretenses” to stir up unrest and conspire against the government.

This bears a remarkable similarity to right-wing governments characterizing all forms of resistance to the mainstream ,“Communist”, “Antifa” or “Domestic Terrorism”. Believing everything we read about the White Lotus is a bit like believing everything you hear about leftists on conservative news stations. The truth matters less than the effectiveness of the propaganda.

Return to the birthless

In addition to Maitreya and other Bodhisattvas and sages, the White Lotus sects worshipped a “mother goddess”, Wusheng Laomu 無生老母 (“Birthless Old Mother”) who represented the wisdom of primordial emptiness and was associated with even more ancient female deities in Chinese folk religion. Wusheng Laomu was seen as the progenitor of all Buddhas, dharmas, beings and phenomena. The purpose of devotion to her was a return to the freedom and bliss of emptiness, or in the common parlance, “heaven”. I am reminded of the saying, which I think originated with David Graeber, that amargi, the Sumerian word which is the first known example of a term for freedom translates literally as “return to the mother”.

Egalitarianism is a remarkably consistent value of mother goddess-worshiping peoples throughout history, at least in comparison to cultures which center patriarchal deities. Chu argued that egalitarianism, between classes but particularly between the sexes, was a distinctive feature of the White Lotus belief that “all people were the children of the Eternal Mother”. Chu also writes that “In many White Lotus movements throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties women were active as fighters and group leaders. The first sizable White Lotus uprising during the Ming was led by a Shandong (Shantung) woman, Tang Sai-er. Noted for her prowess in Taoist magical arts, Tang mobilized a revolt that swept across the province in 1420.” Tang Sai-er herself was said to have a direct connection to the primal mother Wusheng Laomu which was the source of her magical powers.

And while tame by modern standards, the nocturnal “incense gatherings” common to most White Lotus societies were equally open for men and women to participate and socialize freely as “virtuous friends”, which was seen by mainstream society as extremely scandalous and subversive to public morality. Members of the sect were taught that all men and women who believed in the White Lotus teachings would become Buddhas and Buddha-mothers.

Economic egalitarianism was also evident in the practices of some White Lotus sects. By the 1300s the White Lotus societies had accumulated vast wealth through various means: They collected membership dues, managed business enterprises, and to the irritation of officials, “pretended to be ‘doctors’ or’ fortune tellers’, or act as merchants, and go everywhere to evangelize and collect money.” Of course much of the money was thanks to the donations of their wealthiest members, often the hereditary leadership, who could afford to fund buildings and hire private armies to fight for them. They were, on the whole a highly hierarchical organization, what we would understand today as a cult, which nonetheless practiced downward (and probably some upward) economic redistribution among its membership. In good times and bad members of the society could also count upon their brethren for welfare and mutual help when they fell upon difficulties. Flowers goes farther, arguing that most of the White Lotus societies, “practiced a form of mutual aid, even communism”. During times of revolution there were instances of mutual aid between liberated regions and “hints” of the collectivization of property.

Red revolt

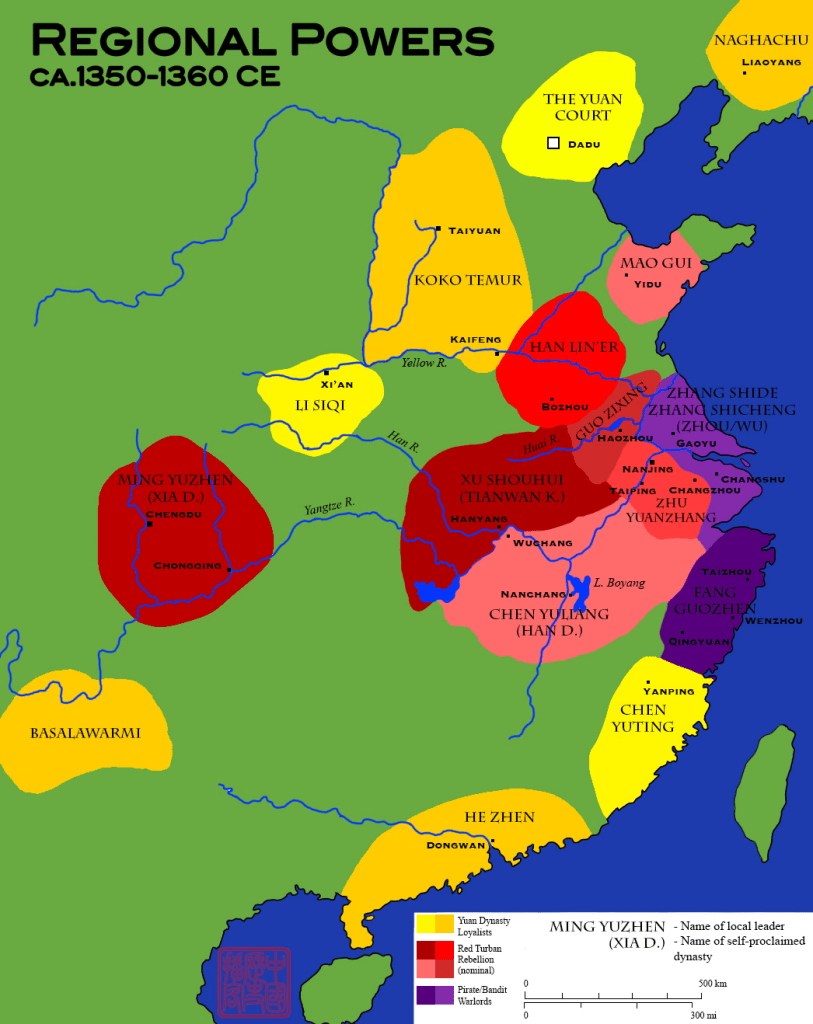

The first significant revolution led by White Lotus Societies is known as the Red Turban Rebellion, named after the red scarves worn by its fighters. It might be more accurately described as a series of rebellions leading to a revolution which overthrew the Yuan Dynasty and inaugurated the Ming Dynasty. Frederick Mote writes that “The rebellions themselves were the final stage of a long history of Chinese resentment against Mongol rule, expressed at the elite level by reluctance to serve in the government and at the popular level by clandestine sectarian activity. The occasion for the rebellions was the failure of the Yuan regime to cope with widespread famine in the 1340s.”

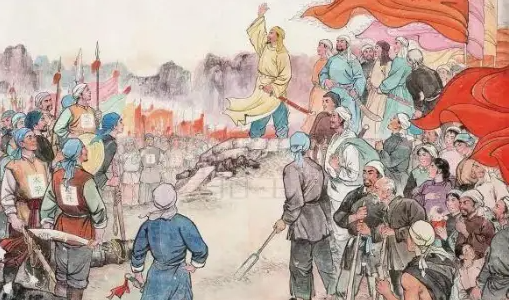

The initial spark came from a Buddhist monk named Peng Yingyu, who instigated and uprising in Jianxi in 1338. This uprising was put down, but Peng survived to spread his Millenarian doctrine to other regions. He is credited with transforming the ancient Maitreyan beliefs into a “potent ideology of social action”. Soon prophets, popular militias and secret societies began popping up all throughout China to challenge the weakening Yuan regime. The White Lotus ideology and organizational network acted as an “axis” to unite and coordinate the various rebel groups in the Southwestern and Northeastern provinces. The incense gatherings of the White Lotus were to become the seeds of the so-called “incense armies” that would openly challenge the government. This eclectic assemblage of merchants, monks, grifters, wizards, martial artists, peasants and prophets — regular people, in other words — had awakened.

The Red Turban movement found fuel for its growing fire In 1351, when the government conscripted 150,000 peasants and workers to work on a “megaproject” to change the course of the Yellow River, which had been the site of devastating floods in 1344, and to re-open the Grand Canal in Shandong. This, amidst the chaos and suffering of the era, was spectacularly unpopular with the conscriptable workers and their families. Influential Red Turban/White Lotus leaders took advantage of the public reaction to instigate a rebellion against the Yuan. The leaders of this rebellion, Han Shantong and Liu Futong, intended to reestablish the Song Dynasty (with Han Shantong as emperor and “Lord of Light”, of course) and expel the occupying Mongol government. Han Shantong was killed by the government, but his wife and son escaped with the help of Liu, who established a new rebel “capital” at Yingzhou and installed Han’s son, Han Lin’er as the nominal child emperor and “little” Lord of Light.

Meanwhile, to the south of the Huai River Peng Yingyu had managed to attract a significant following with the military force to match. Sensing that his movement was still lacking a certain millenarian vigor, he made a figurehead “messiah” out of an extremely ordinary cloth merchant named Xu, who he claimed was the incarnation of Maitreya Buddha, descended from heaven to “destroy the rich in order to benefit the poor” and establish his own new dynasty. With a popular figurehead in play their movement grew exponentially.

At this point, as with many grassroots revolutions which get too big too fast, the power games began. The military and political leaders of the Red Turbans could see that one way or another, the Yuan were going down. What mattered the most, now, was determining who would come out on top to seize the “Mandate of Heaven” to establish a new imperial government. In one of History’s interesting twists, the Mandate would end up falling to an ex-monk and young soldier named Zhu Yuanzhang, who rose out of dire poverty and up through the ranks of the Red Turban army to eventually become the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming Dynasty in 1368. As such things often go, the Ming quickly turned on the White Lotus societies and resumed the Yuan’s campaign of persecution. However, for the White Lotus as a revolutionary vehicle this was more of a beginning than an end.

In one of the endless ironies of history, the Hongwu emperor’s grandson and successor pursued the exact same policy of mass conscription to rebuild the Grand Canal which inspired the rebellion that brought his grandfather to power. He was opposed by the armies of the White Lotus, led by renowned martial artist and sorceress Tang Sai-er. Though this rebellion was eventually defeated, Tang Sai-er was never captured. The Lotus continued to grow beneath the mud, waiting for another revolution to bloom.

Rebellions inspired or organized by White Lotus ideology would be a continuous threat to all successive dynasties until at least the 1804 Nian Rebellion and the 1813 “Eight Trigrams” Rebellion. The so-called White Lotus ideology remained a potent revolutionary force throughout Chinese history up until the modern era. It is likely that anarchism and later communism captured most of the peasant demographic previously organized by the White Lotus, and the acceleration of modernity has further modified the social basis of these organizations. But if this loss of a mass base represents a social evolutionary threshold or is simply a lull in a normative cycle is yet to be seen. The cult’s extensive 1,400 year history gives us reason to pause before definitively proclaiming its end.

Gather at night, disperse at dawn

If the end result of the Red Turban’s revolution doesn’t make this clear, I’ll spell it out: we should be careful to not map modern social theories too closely over ancient ones. If we are looking for a socialist revolution in the Medieval world we are not going to find one. The White Lotus rebels by no means advocated for the abolition of classes and states or their replacement with self-managing democratic communes. Their theory of change centered on a prophecy of salvation and dynastic renewal by a divine leader. As we see in the story the end result of the Red Turban revolution was the foundation of a new Imperial dynasty, not freedom as we might understand it. The White Lotus provided the impetus for the uprising but was ultimately marginalized by more savvy political actors from within its ranks.

Limited by their religious dogmas and ideas available in their context, Chu wrote that the White Lotus failed to create “concrete programs to meet the practical social, political, and economic problems of Chinese traditional society. Thus rebеllious movements under its leadership never succeeded in establishing an enduring and revolutionary regime.” However, “The fact that this association managed to retain its spirit of resistance down through the ages suggests its importance as a vehicle of continuity.” The rebellion may have been put down (or incorporated into the state), but the secret practices of the sects, the flame of the incense or the candle, continued to be passed down and inherited in secret.

Unlike the modern revolutionary left, however, White Lotus societies managed to survive, evolve and even flourish under conditions of severe repression for a period of at least 500 years (more like 2,000 if you consider the founding of the first White Lotus School and continuity with earlier Taoist-inspired rebellions). This remarkable example of continuity may provide lessons for contemporary radicals, who often struggle to preserve their tradition beyond a couple of generations. Socialism and all its quarreling sects are themselves no more than 200 years old at best.

So what did this “vehicle of continuity” contain, and where did it go? Societies and syncretic folk religions bearing the lineage of the White Lotus still exist today, though to my knowledge none are the least bit revolutionary. It seems that torch has been passed. But to whom?

Ngo Van concluded his survey of Chinese peasant rebellions, that “In China, as in the West, utopia, so deeply rooted among the dispossessed, proceeds from a popular understanding of emancipation whose memory must be preserved, before it disappears in the tortuous and brutal adaptations to economic modernity that perpetuate the burden of the coercions of the past.”

Buddhist influence on the Chinese socialist movement could have come from the memory of popular power which the White Lotus rebellions represented. Without a doubt Taixu, who was himself a devotee of Maitreya, was a spiritual descendent of this lineage, though indirectly. More likely than not the anarchists of Guangzhou, who organized themselves in secret societies and were familiar enough with Buddhist doctrine to use it in their propaganda also inherited some of the heretical spirit of the White Lotus.

Marxist scholars in China have often struggled with the contradictory implications of the White Lotus and its practices due to the religious, cross-class and seemingly backwards aims of these rebellions. But a more broad minded analysis of the function of the religious mode in revolutionary social change leaves many doors open for analysis. The influence of the White Lotus movement persists even today due to its deep cultural roots, roots which are now global. After all, much of what the world understands of “Kung Fu” (which means, apparently, literally any skill mastered through practice, not just fighting), transmitted by popular media and its physical practice, stems from innovations in physical and magical culture made by members of White Lotus sects.

I am far from the only one who has seen the seeds of modern revolution in the sects and secret societies of the past. In fact much of the European socialist movement has its origins in secret societies devoted to occult ritual, enlightenment philosophy and working class resistance. In Occult Features of Anarchism Erica Lagalisse retraces the little-known journey of European radicals from membership in occult fraternities like the Freemasons — and even the infamous “Illuminati” (whose name simply means, “the enlightened”) — into the first clandestine workers associations and unions. Though they left behind the occultism, they adapted some of the organizational strategies of the secret societies to plant the seeds of revolutionary socialism within mass movements. Bakunin famously organized the (semi-)secret “International Alliance of Socialist Democracy” in order to collectively join and radicalize the International Worker’s Association. They succeeded in converting most of the IWA national sections to some form of anarchism. This strategy, called “organizational dualism”, has been a consistent current within the anarchist movement up to the present day and has proved to be one of the most useful and consistent methods for anarchists to maintain a strong presence in mass movements. While I have not been able to find any direct evidence of Buddhist secret societies influencing the first socialist revolutionaries, it would be reasonable to infer from the European example that such an influence would have been plausible at the very least.

But did these anarchists perhaps make a mistake by eliminating all traces of the occult from within their organizations? Rationality, atheism, secularism and science certainly played a progressive role in the revolutions of the 19th and 20th century. But in the fragmented, meaningless and hopeless mood of the 2020’s might we once again find some use for magic, belief, ritual and belonging? I ask this not because I believe in the supernatural. But it is obvious that current movements face a crisis of motivation and a crisis of unity. Modern socialism, in my view, is too “dry”. A common strength of the occult and religious movements are their ability to help people, for better or worse, to overcome their fear of death and conflict. For any revolution to succeed its participants must feel an almost otherworldly courage in their bones. In the distant past the millenarian peasants believed that magic spells and amulets would make them invulnerable. Others, such as the Red Turbans, thought that the worse the tortures inflicted on them by the state, the “higher their place in heaven”. Some reports claimed that martyrs of these struggles were taught that they would be reborn as accomplished Bodhisattvas in Maitreya’s heaven to wait for the millennium. They were so difficult to repress that even the ever-faithful enemy of the White Lotus, government official Chao Ch’ang-Shen complained that “Not fearful of violating the law or committing seditious acts, as they are eager to return to heaven, they are happy to face capital punishment. Thus, penal sanction is useless in deterring them.”

Modern revolutionary movements are replete in programs to meet the people’s needs, some more concrete than others. What we sorely lack, however, is a comprehensive, popular, and widely accessible system of belief which sustains our spirits through the ages and acts as a “vehicle” of revolutionary continuity. The body may die, but the beautiful idea, the “birthless old mother”, the black flame of rebellion, is as eternal and indestructible as the idea of freedom. The inheritance of this “will” is never a certain thing. Sometimes its “host” dies out completely, and it must migrate inot the sanctuaries of myth, literature, and cultural transmission. The countless tales of commoners skilled in martial arts rising up against the government were passed down in Chinese history as folk tales and Wuxia novels. These developed their own genre-specific cliches and styles. In the modern era they made the leap to the silver screen, and the “Kung Fu” movie genre was born. This trend spread around the world, influencing Hollywood to make its own martial arts action movies and the Japanese animation industry to produce cartoons protagonizing rural martial artists who possessed supernatural powers. As a part of this semi-mythological package, the idea of revolutionary Buddhist societies overthrowing governments has dispersed into global media and popular culture. The story of the White Lotus is probably as much myth as it is fact. But myths are not necessarily untrue. A really good story can propagate itself long after the people who inspired it have departed from the stage of history.

After all, I would also be remiss not to mention the American animated television series “Avatar: The Legend of Korra”. The third season of this series features a secret anarchist revolutionary organization called “The Red Lotus”, which is itself a left-wing split from an international “White Lotus” secret society which once opposed an occupying imperial power. The members of the Red Lotus are adept sorcerers and martial artists. Their beliefs stem from the teachings of the fictional “Guru Laghima”, whose philosophy resembles a mixture of Buddhism and Bakuninist anarchism. One of the guru’s quoted sayings paraphrases Bakunin’s famous quotation: “The urge to destroy is also a creative urge.”

Apocalypse vs the commune of maitreya

There are many illustrative analogies which can be made to connect the White Lotus Society to modern revolutionary organizations. Any experienced social militant is likely to find a familiar flavor to the activities and inclinations of the White Lotus members. Surely many could imagine meeting secretly with “virtuous friends” to burn incense and candles in the dead of night. But could we imagine willingly enduring the torturous execution by “slow-slicing” faced by sect members, the years of fighting, the centuries of repression, committing to passing down of a sacred flame of freedom in secrecy and darkness? Not that these are ideals to strive for, of course. But in times of great trouble the collective capacity for great courage and great forbearance will no doubt prove decisive in struggles against powerful adversaries. Especially when the most powerful adversaries of our age are intangible and seemingly omnipresent: states, corporations, ideologies; despair, alienation and fear. These abstract entities, however remote, are instantiated in bodies of flesh and blood. As such, a much more potent exorcism may be necessary to drive these ills from the social body. “Agitate, educate, organize” was a good enough formula for motivating the oppressed subjects of the 19th and 20th centuries, and obviously still has a high level of efficacy in many contexts. But on the level of mass-consciousness, we may be approaching thresholds of technologically-mediated domination and resistance capacity in human beings for which rational argument fails to communicate at scale and across contexts the urgency and severity of crisis. We are approaching turbulent times which may make the 14th century collapse look tame in comparison. If relatively minor climate changes could bring about a century of near-universal misery then whatever the 21st and 22nd centuries are in store for will likely be apocalyptic in ways we have no real analogues for.

To participate in a revolutionary science of survival, the “vital human potentials” held within Buddhism must be stimulated into fuel for the fight. In 13th Century China, the dualistic struggle between the cosmic forces of good and evil provided the Buddhist underground with the necessary accelerant to burn the Yuan to the ground. But as Chu points out, the “destructive urge” of the Red Turban incense armies failed to transmute itself, as in the Bakuninist formula, into the “creative urge” of social revolution. Radical social theories (socialism, anarchism, ecology, feminism, etc), should they find the sodden fuel of Buddhist potential, may prove better accelerants than the Manichean prophecies. But only if we are willing to tell a better story of the conflict between good and evil.

Anarchism is motivated by compelling conflict narrative, but it can be overly abstract at times and too literal at others. It is inherently self-limiting in terms of the audience it wishes to convert. Buddhism is for its part just as stubbornly insistent in its rejection of conflict. But when viewed through the eye of the other, something very interesting emerges: a story where there is a battle between good and evil for the fate of sentience. In this saga, good and evil are scale-independent. They both arise out of the matter of basal cognition and have been in conflict since time immemorial.

Evil, Buddhism could tell us, is the egoistic, ignorant, dominating, all-consuming and terrified “I” which claims dominion over mind, body and world to do with as it pleases. It is personified in myth as the demon Mara. This character is found everywhere, from the self-obsession of the cancer cell, to the mind of the sociopath and the abstract intelligence of the capitalist system itself. If left unchecked, it will consume and destroy everything which it does not recognize as “self” before finally consuming itself. Good, for its part, is the name we give to the eusocial and developmental impulse of living things: It is the symbiosis of the eukaryotic cell enabled by communication, cooperation and care between its constitutive, formerly independent elements; It is the empathetic recognition between child, mother and “other” which enabled the formation of sociality and thus the human intelligence explosion; it is the mutual aid and solidarity which enables communal life to flourish; it is the radical openness, the emptiness, the boundless potential of courage and compassion which we call freedom.

This is the struggle in which we find ourselves today, at long last able to perceive its true depth. Cooperation or Competition. Domination or Freedom. Incarceration or Emptiness. These are the terms by which we must draw our lines. Only a Buddha could hope to defeat such a universal foe. Maitreya is needed once again.

On the vast scales of social abstraction inherent to a global society of billions, the echoes of myth, magic and prophecy may regain the potency stripped from them by scientific modernity without discarding the revolutionary potential of science. In the 20th century Taixu speculated that Maitreya, the future Buddha, may in fact be a collective entity. Drawing equally on the motivational power of higher-order mythic archetypes and the explanatory power of scientific inquiry, what kind of “Maitreya” and what kind of “Pure Land” could we manifest to save this burning world?

Sources

- Wallis, Glenn. “Heresy: A Non-Buddhist Guide”. (2025)

- Văn, Ngô “Ancient Utopia and Peasant Revolts in China” (2004)

- Junqing, Wu. “The Fang La Rebellion and the Song Anti-Heresy Discourse” Journal of Chinese Religions, vol. 45 no. 1, 2017, p. 19-37. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/708126.

- Corrêa, Felipe. “An Historiography of Anarchism” (2023). https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/felipe-correa-an-historiography-of-anarchism

- The China History Podcast, Episodes 194-195: https://thehistoryofchina.wordpress.com/2020/07/17/195-yuan-13-the-lords-of-light/

- Haar, B. J. t. (1999). The White Lotus Teachings in Chinese Religious History. United States: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Theobald, Ulrich: Bailian jiao 白蓮教, the White Lotus Sect http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/bailian.html

- Heathen Chinese. “Millenarianism Pt. 4: The White Lotus Society And The Nian Rebellion” (2015) https://heathenchinese.wordpress.com/2015/01/03/millenarianism-pt-4-the-white-lotus-society-and-the-nian-rebellion/

- Flower, Theresa J. (1976). Millenarian themes in the White Lotus Society (Thesis). McMaster University. https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/7251/1/fulltext.pdf

- Chu, R.Y D. (1967) “An introductory study of the White Lotus Sect in Chinese history with special reference to peasant movements.” Ph.D. dissertation. Columbia University. https://www.proquest.com/openview/5f89aaf9a378bcb8421d81149bc715a2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Graeber, David. “To Have is to Owe”. (2010) https://davidgraeber.org/articles/to-have-is-to-owe/

- Mote, Frederick W. (1988). “The rise of the Ming dynasty, 1330–1367”. In Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–57. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Gillis, William. “An Anarchist Perspective on the Red Lotus” (2014) https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/william-gillis-an-anarchist-perspective-on-the-red-lotus

- Lagalisse, Erica. Occult Features of Anarchism: With Attention to the Conspiracy of Kings and the Conspiracy of the Peoples. 2019. PM Press.

- Killjoy, Margaret. “Cool People Who Did Cool Stuff Podcast: Part One: Secret Societies and Leftism: The Odd Origins of Revolution“. October 12, 2025.

- Judkins, Ben “Ming Tales of Female Warriors: Searching for the Origins of Yim Wing Chun and Ng Moy.” Kung Fu Tea (2013) https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2013/06/21/ming-tales-of-female-warriors-searching-for-the-origins-of-yim-wing-chun-and-ng-moy/

- Ritzinger, J. R. (2014). The Awakening of Faith in Anarchism: A Forgotten Chapter in the Chinese Buddhist Encounter with Modernity. Politics, Religion & Ideology, 15(2), 224–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2014.898430

- Federacion Anarquista Rio de Janeiro. “Social Anarchism and Organisation” (2008)

- Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer. Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Doctor, T., Witkowski, O., Solomonova, E., Duane, B., & Levin, M. (2022). Biology, Buddhism, and AI: Care as the Driver of Intelligence. Entropy, 24(5), 710. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24050710

- Levin M (2019) The Computational Boundary of a “Self”: Developmental Bioelectricity Drives Multicellularity and Scale-Free Cognition. Front. Psychol. 10:2688. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02688

Great article. 👍

Probably, Nichiren came closest to formulating an insurectionary Buddhism. He wasn’t an anarchist, but his ideas might still be worth looking into.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was thinking that the Japanese Pure Land would be my next deep dive into the millenarian tradition, followed by the Donghak uprising in Korea. Honen, Shinran, Nichiren,and the Ikko Ikki militas would all be an intersting comparison. Any recommended readings?

LikeLike